Botin Partner's first Class40

The Class40 race will certainly be the one to watch in the Transat Jacques Vabre, which is now due to exit Le Havre on Monday with the starts for the Class40 and IMOCA 60 monohulls, before the Multi50s and MOD70s set sail later in the week.

Among the impressive fleet of 26 Class40s are a number of not only new boats, but new designs and new designers to class. Alongside the new offerings from Jason Ker and Tom Humphreys, a boat which is also expected to be among the frontrunners is Gonzalo Botin’s Tales Santander 2014, being campaigned in the race by Spanish duo Alex Pella and former 470 sailor Pablo Santurde. This is Gonzalo Botin’s second Class40 having previously owned a modified Akilaria which subsequently became the second generation RC2.

The boat has been designed by the elder Botin brother Marcellino, who runs Botin Partners out of Santander (from where his family’s famous banking dynasty heralds). Botin Partners were responsible for the Camper VO70 and this is their first foray into Class40, the new boat built by Longitud Cero near Valencia, where most of their TP52s have been constructed. It was built to Cat 0 so that it can be raced around the world.

Antonio Piris (left) with Gonzalo Botin.

TJV crew - Alex Pella (left) with Pablo Santurde

Antonio Piris, one of Spain’s leading project managers and sailors (including Whitbreads on Galicia Pescanova and Chessie Racing and a Barcelona World Race doublehanded), managed the build of the new boat, and says its first conception came after the Tales crew had blown away by some of the newer designs: “We were quite amazed by the speed of the Manuard boats especially GDF Suez and its earlier sisterships, mare and particularly Jack in a Box. Two years ago at the Worlds, that boat just passed us on a reach like we were in another class – two knots faster! You could see they were 5° less heeled and with the leech of the main much further in, so it was raw power. Since then all the new generation boats have been very very conscious about the Manuard boats.” See our video guided tour to the Mach40 mare here.

The early Manuard Mach 40s originally had adjustable rake on their rigs (something since prohibited) however Piris thinks it wasn’t this that was contributing to their impressive pace. “They were the lightest displacement with a lot of hull stability and the centre of gravity of the mast was really low with the spreaders really low – that looks strange, but it works as it allows you to carry a smaller bulb, while still having the maximum stability allowed in the class.”

While the majority of Class40s are production or at least semi-production builds, the new Spanish boat is an uncompromising one-off, although full tooling exists – the hull was built over a male plug, but almost everything else came from female moulds – so more could be built.

The Class40 box rule includes a minimum weight limit of 4,500kg, maximum beam of 4.5m and also a 90° inclination test to determine righting moment - at a measurement point close to the masthead there can be 235-320kgf of positive lift and most designers gun for maximum righting moment, ie the higher limit.

According to Botin Partner’s Adolfo Carrau their aim was to achieve maximum righting moment, but minimum displacement, while also attempting to reduce the wetted surface area of the bulb. This, he observes, is similar to how they used to optimise TP52s under the original incarnation of that rule. He believes their new boat has the smallest bulb in the Class40 fleet.

To achieve this, one of the keys to the Spanish boat is her keel fin, which in addition to its steel structure, contains lead – there are compartments within both the fin and bulb to which lead inserts can added or subtracted, so that the stability can be fine tuned to hit maximum stability exactly.

“The keel construction is pretty complex,” admits Carrau. “The rule doesn’t allow you to CNC mill the keel, so you have to do all the fairing by hand. CNC milling would have been done in two weeks. This took forever.”

The keel bulb and fin were built by APM in Italy, known for building some of the world’s biggest superyacht keels.

While offshore boats like this are typically optimised for reaching, the Botin design has a good all-round performance as she demonstrated in the Rolex Fastnet Race when she led the Class40 fleet around the rock, only to be overhauled by the Manuard-designed GDF Suez on the run into Plymouth. The boat’s performance is solid upwind, but equally competitive power reaching, which, Carrau observes is when the fully optimised Class40s that have maximised their stability really come into their own.

The Class40 is intended as a semi-professional class and has a rule written accordingly (although efforts are being made to tighten it up, while also reigning in costs). As a result there were a few issues applying a high end Grand Prix race boat approach to putting the boat together –15-16 designers and engineers worked on the project for three months, while construction of the boat took an age for a 40 footer – around eight months.

“We did a full CFD and VPP research like we did with the VO70, only not as long,” says Carrau. This included working with their ‘partners’ such as Giovanni Belgrano’s company Pure Design & Engineering in New Zealand.

The philosophy behind the internal structure was to minimise transverse bulkheads (within what is permitted in the class rule) and focussing more on longitudinals, the aim being to make it as easy as possible to move the stack fore and aft. The longitudinals have an Ω shape to them, the reasons for which Piris explains: “That takes a long time to build, but is really light and stiff and then it is just filled in with foam in between to comply with the buoyancy rules. It is all Sikaflexed in, in case we need to check for delamination.”

The bulkhead forward of the main one, has an unusual triangular shaped aperture in it.

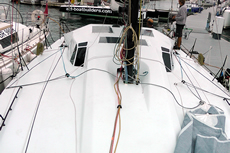

The hull shape of the Botin Class40 follows the modern trend of minimising freeboard (the rule has a minimum average freeboard which the latest boats are hitting) while having a powerful forward section (new rules were introduced last year to prevent a Class40 scow being built). There is also the now obligatory ‘chamfer’ – the angled hull to deck join – which also assists in getting boats through the 90° inclination test.

During the design process Botin & Partners found they had to dust off their data on building in glass as the now standard race boat construction of carbon/Nomex is prohibited by the class for reasons of cost. Carrau says that thanks to the amount of man hours that went into building the boat in glass - with a wet lay-up and vacuum bagged - in fact it ended up costing only a fraction less than if they had built in carbon/Nomex. “If you do it like a high end racing boat, then pre-preg carbon is not that more expensive and it would result in a much faster boat.”

However he acknowledges that the Class40 rule was written to promote production building and even amateur construction (although none racing in the TJV are home builds).

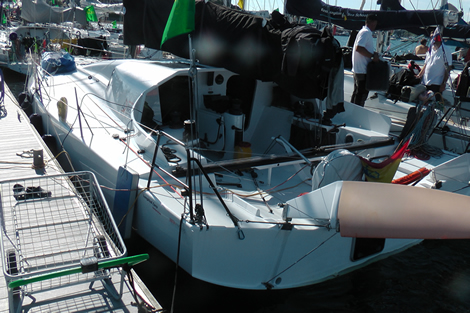

The Botin design is also set up so that it can be raced inshore – it came as a big disappointment to the team that they were unable to defend their World Championship title, after this year’s event was canned - it had been due to be held in Plymouth at the end of the Fastnet. So, for example, the cockpit protection around the sides of the cockroof can be removed.

For this purpose the boat is also fitted with a vang. Piris shares the reasoning for this: “Many other Class40s don’t have a vang, which I found it really frustrating when you are doing short courses and you are gybing - the battens don’t go through unless you put on the vang, but you can’t put the vang on until you have finished with the gybe. So it takes a long time.

"Also you cannot pump your main because every time you pump you have to release the vang and you never find the balance, and we didn’t want that. So we went for a slightly heavier boom and we put a fuse in the vang. So when its heavy weather, we don’t mind if we break the fuse, but when the weather is okay it means we can pump and make good use of the main. Of course, the boom sits a little bit higher and you lose some mainsail area, but because the maximum sail area is main and jib combined (115sqm), we could maximise the jib area.”

The mast is from Franco-Romanian company Axxon Composites, run by Eric Duchemin, formerly with Lorimar, and with whom Piris had previously worked when he (Piris) had project managed the series of Caixa Galicia TP52s.

The mast is deck stepped, simply, Piris explains, because the engineers found this to be the lightest solution, but it has the added advantage of being a more water tight solution. The vertical centre of the gravity of the mast is as low as possible.

Piris adds: “You don’t need the mast to be keel stepped because you are not moving the forestay and you’re not playing with deflection. The mainsail is naturally flat, you aren’t bending your mast or blading your main, you just have to be able to reef.”

The mast step itself fits into a recess in the forward end of the cabin top, enabled them to fit the vang.

The spreaders are long and swept back and there are no hydraulics or hooks to contend with as there are on bigger boats, as, again, they are prohibited under the Class40 rule. There are no jibs tracks, instead there is the now common laterally barber hauler arrangement with a flying ring setting the lateral position of the clew.

The sail wardrobe is from Juan Meseguer of North Sails Spain, who worked with the team on their first Class40. Class40s are allowed to carry eight sails, two of them built in exotics, in Tales’ case in carbon 3Di. Typically the sail wardrobe comprises main, genoa/jib/Solent, staysail, storm jib and four sails for off the wind work. On Tales Sandander 2014 they carry a Code 0, A2, A3 and there is a choice of a smaller Code 5 or A6, depending on the weather anticipated for a race.

Most Class40s are fitted with a rotating bowsprit that enables the clew of the kites to be brought up to weather, a kind of A-sail version of squaring the pole, enabled deeper angles to be sailed downwind. The aluminium cup around which the bowsprit swivels is mounted right on the tip of the bow with the forestay going through the middle of it to maximise the J measurement. Tack lines neatly feed into the sprit and emerge at its forward end, while the aft end of the sprit is mounted on a semi-circular track to help control its rotation.

The twin rudders are kick-up, however unlike the common IMOCA 60 system where the rudder kick-up mechanism is built into the hull, where the blades end up under the counter, on the Class40s they are all transom-hung, as the IMOCA 60 method is thought to be too heavy for the small boat. Piris admits that the kick-up mechanism (a notorious weak spot on some boats) was inspired by the Sam Manuard-designed Mach 40. “We looked at the competition and we couldn’t find a lighter solution.”

The cockpit layout, is also very Manuard-like and features a central pit area, the lines tunnelled aft from the mast step, with two small companionways either side. The main sheet also emerges into the pit. “Usually it goes out to one side or the other and then you can go for four winches, but that is less user-friendly,” says Piris of the main sheet.

The cockpit is open ended to allow water to drain aft, but the crew is kept in the forward part of the cockpit thanks to the elevated main sheet track that spans almost the full beam of the boat. While there is are twin rudders, these are operated by a single tiller. All electronics on board, including the all-important autopilot, are by NKE.

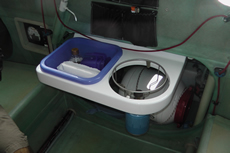

Down below, the finish is immaculate, but the layout very spartan, while complying with Class40 rules, including for example four fixed berths (ie not pipecots) and a chemical toilet forward. There is panel for the nav instruments aft of the main bulkhead including a small table for a computer keyboard - the whole rotates so the navigator can do his job while sitting to windward. The galley slides out from under the forward end of the cockpit and comes with a small plastic washbasin and single burner Camping gas stove. The 'saloon' area is well illuminated thanks to two forward facing windows having been fitted where the cabintop flares out, jib sheet tackle.

There are two shallow water ballast tanks each side and these extend most of the way aft to the transom. Typically the forward tank gets filled first. Unlike some of the other new designs (which dump water and then simply bring it on board afresh on the new tack), a substantial transfer pipe is fitted, allowing water to be dumped to the leeward tank before tacking.

The downside of going for a fully custom Class40 is of course cost and to get a second of these Botin Class40s would come with a price tag of around 500-600,000 Euros, although with all the tooling now in place, the build time could now be halved to around four months.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Latest Comments

Add a comment - Members log in