Ian Walker on the Volvo Ocean Race

Three legs down into Ian Walker’s third Volvo Ocean Race and Abu Dhabi Ocean Racing is lying in a comfortable second place, one point behind overall leader Dongfeng Race Team.

“We are in rude health,” says Walker. “I am pretty happy with the results so far. We have made some steps up in how we’re sailing the boat. Everyone is fit and healthy, we are crossing off the miles, avoiding disasters and racking up some good results. It couldn’t be better really.”

The latest Volvo Ocean Race is of course being sailed in the one design VO65s and this is placing even greater emphasis on meticulous crew work - how the boat is trimmed and steered, how the keel canted and the amount of daggerboard to be used, the configuration of the water ballast and stacking, plus of course the all-important crossover chart determining sail changes - and all of this for every wind angle and wind speed. This represents a never-ending learning curve.

“The boats seem pretty twitchy,” says Walker. “It is remarkable how big the speed differences are between the boats at times. I don’t think it is an exaggeration to say that ‘the team that learns the most is probably going to be the one that prevails at the end of the race’, because we are all starting from a fairly low base.”

Traditionally two boat testing has been the best way to determine out to get 100% out of a boat, but, in the name of cost-saving, this was prohibited prior to the start of this Volvo Ocean Race. Walker cites this as one of the less obvious reasons boats have been sticking together during the race so far. “I think Brunel and Dongfeng did a good job of sailing with each other on leg two, because that is the only way you learn,” he says. “The last leg was really good for us, because we sailed for two weeks in sight of two or three or even four boats.”

Thankfully no one boat seems to have come out of the mould better than any of the others, as Walker states: “They are probably the most ‘one design’ boats in the world. I’d say they are more ‘one design’ than the Laser - the mast is the same, the CoG of the rig is the same, the keel, fin and bulb are the same weight. If you lose faith in the [one design nature of the] boat – which I haven’t – then you question everything. It’s certainly the case that when you are not going well, you have to take a long hard look at yourself, and you can make improvements. We have not found any conditions where we couldn’t solve the riddle eventually - it has just taken us a while on a few things.”

Even if the boats are not directly alongside one another, crews can still monitor the progress of competitors nearby by tracking them on AIS. A significant new feature of this race is the requirement that boats keep their AIS on at all times. In the last race they had to be able to receive AIS at all times, but didn’t have to actively transmit AIS data unless the SIs required it – in places like Malacca and Singapore Strait. “There were certain areas where you had to switch it on, apart from Groupama - who was sending the whole time! We could always see them – but no one told them! Anyway, it didn’t help us – they still won…” recalls Walker.

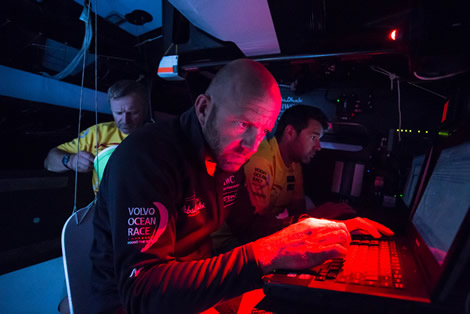

So this time round crews receive the six hourly scheds (rather than three hourly), but these are now more or less redundant because with AIS plumbed into each boat’s nav software provides the ability to track each target (ie boat), allowing each crew to see the speed and course of their immediate competitors in real time. Plus it works at night. The limit is the range of AIS, which for the VO65s turns out to be around 10 miles.

“The whole advent of AIS has changed offshore racing,” states Walker. “The whole business of whether you are within 10 miles of another boat or not makes such a huge difference to how much you can learn from the other boats. But it has become a bit of an obsession. We started to try and look at it less, because it drives you mad!”

Sailing with a crew of eight this time, the watch system has had to change and on board Abu Dhabi Ocean Racing they are running rolling watches of two with Walker and navigator Simon Fisher standing watches, rather than being officially out of the watch system.

Typically the nav happens at watch changes. “SiFi stays down normally for the first hour of his watch, but he is ready to go, although it depends on the conditions. If you are sailing upwind you only need two or three people on deck, but if it is windy downwind, then more hands on deck are needed. But there is generally less nav work needed when you are windy downwind conditions than in the light, fiddly stuff.”

In fact so far in this race, the nav station hasn’t been the ideal place to navigate from. Instead the deck screen has been getting considerable usage. “Because it has been mainly light winds, the reality is that you haven’t been in the nav station because it is too far aft and we’ve all been living on the bow and on the foredeck. So you end up using the remote screen on the bow or in the bow.”

While the advent of AIS in the race has been one reason the fleet has stuck together, it is also because for the most part the boats that have separated from the pack have ended up losing out.

“It is really strange, I have to say - there is a herd-like mentality,” admits Walker. “Everyone has the same mantra: ‘Stay with the fleet, then you’ll learn more’. Certainly if you imagine being in the de-brief of Alvimedica and MAPFRE - they got separated from the fleet and made big losses, so I’m sure they are being told to stay with the fleet, and SCA, the same.

“Quite often I can see the fleet going the wrong way, because everyone is waiting for someone else to tack or to gybe. Like on the last leg, there were a lot of routing solutions that were down the Indian coastline, which were significantly faster than where we all went, but there was no way you’d dare go there on your own. It is quite bizarre really.”

Looking forwards on the one hand it seems likely that the fleet will get closer and closer as each crew learns to sail their yacht as close as possible to 100%. However, conversely, as the race progresses, those down the leaderboard may feel less compunction to stick with the pack, with the potential for magnificent fliers to be taken, just as backmarker Brunel Sunergy did successfully on two occasions in the 1997-8 race.

While the VO65s have proved to be evenly matched, they have also proven robust and generally quite reliable. “They are heavy and strong and that’s what they wanted. I think structure-wise, they have been pretty good, but that doesn’t mean they won’t ever break – all boats will break…”

According to Walker, on the last leg they broke the J1 lock (just as MAPFRE did on leg two) and in a previous stopover they had to replace a daggerboard that had sustained some damage, but other than that their boat has remained solid. Dongfeng has suffered some mast track issues, but Walker reckons that this has been due to overbending the mast.

“I am probably more concerned on the mast than anything. They have had some track issues and they put in some reinforcement on the spreader roots in Alicante before the start.” In fact Team SCA actually replaced their mast prior to the start.

Due to liability issues over the new one design, there are load sensors dotted around the boat, data from which is logged and then must be submitted to Volvo. There is also a warning light in the cockpit illuminates when loads are exceeded on certain components. “Most of the time we just put some tape over it!” quips Walker. However, seriously, he admits that they have learned from it. “There are certain times we have exceeded the load because of things we’ve been doing and we have altered what we do to try and avoid that, so there has been some benefit to it. But like all these projects, to see the full benefit you have got to put a lot of time and resource into it and unless you are 100% confident of how everything is calibrated and maintained...”

It has also proved useful because this time around, with the one design, teams have had no part in tailoring the boat to their requirements. “We haven’t made any decisions about what to strengthen up. We don’t know what the redundancy there is on a lot of things - it is unusual to be sailing a boat which you don’t know much about. But you can ask some questions – is the deck strong enough to cross sheet, if the runner winch breaks? Can I put the runner on the pit winch?”

However to date, apart from a few days in the Southern Ocean, arriving at and leaving Cape Town, Walker observes that there haven’t really been any big conditions in the race and fertain none upwind. With leg four – starting from Sanya this Sunday and heading down the globe to Auckland – this is all set to change with much more upwind work and reaching, with breeze expected out of the start.

For this leg Phil Harmer (aka ‘Wendy’) is back and the legend that is Neal McDonald is stepping off the boat to resume he role purely as the team’s Performance Manager. “He was my watch partner so we had quite a laugh,” says Walker of leg 3. “We’ve become quite dependent on him. He has a good perspective and it will be even better now having done a leg.

“Neal is also a bit of a secret weapon for us. Even I didn’t realise how helpful it would be to have someone technically-minded, because you don’t have a design team. Normally if you need a CAD drawing looking at or a project like making sure the rudders are square in the boat or the rig is square or whatever, last time we’d use our sail designer Jeremy Elliot, or the boat designers if they were on site. Now you don’t have that resource so if you want to do any science projects, Neal’s very good at that and there has been a conscious effort to try and take some load off me so that I can go to the gym and concentrate on sailing.”

In part two Ian Walker explains how the new 'Boat Yard' set-up in stopover ports is working and contemplates why Dongfeng is leading.

Latest Comments

Add a comment - Members log in