Nuts and bolts of the VO65

For the first time in its 41 year history, 2014 will see the Volvo Ocean Race contested in one designs – as many as eight of the Farr Yacht Design-penned Volvo Ocean 65s are expected to be on the race’s Alicante start line on 11 October this year.

Abu Dhabi Ocean Racing, with her snazzy paintjob, is the fifth boat off the production line at Green Marine’s facility in Hythe, although Ian Walker’s team is the only fourth to take delivery of their new vessel following on from Dongfeng, Team SCA and Brunel and with Alvamedica believed to be next in line.

After eight years of the brutish VO70s, the VO65 obviously bears great similarity to its forebear (where Farr designed the last generation VO70 for Abu Dhabi Ocean Racing), but also borrows heavily from IMOCA 60s, where the Annapolis-based design house came up with the 2008 Vendee Globe winner Foncia and came home third in the last singlehanded non-stop round the world race with Alex Thomson’s Hugo Boss.

Adopting many IMOCA 60 features has partly come about because, for this Volvo Ocean Race, crews are smaller still - a maximum of eight plus a media crewman (now called the on board reporter or ‘OBR’) permitted for male crews and 11 plus the OBR for all-female crews like Team SCA. Going one design, has allowed a few creature comforts (aka ‘safety features’) to be incorporated into the design.

Obviously gone are the VO70 rule cheats such as the tower for the forestay chainplate and the batwings to raise the runners and spinnaker sheeting points. While the last Abu Dhabi VO70 had the open plan, sidedeck-free, Telefonica Blue-style cockpit, the VO65 has reverted to a more conventional layout.

Particularly noticeable is how much deeper the cockpit seems, with the deck now at knee height. While VO70s used to have a sliding hatch over the companionway but an otherwise flush deck, the 65 has a more prominent IMOCA 60-style coachroof with a small overhang on its aft end. This should at least divert the torrent away from those forward in the cockpit.

There is even a tack-able screen that attaches to the front of the cage surrounding the steering stations to provide protection for the helmsman, although there remains some scepticism about whether this will survive the first night at sea...

All of the fore-sails are now on furlers with the exception of the J1, which remains on hanks and for reasons of handling, but also as a cost-saving measure, there are now only eight sails carried on board at any one time.

Structurally while the VO70s were far from flimsy, the VO65 are huge, built to the highest levels of ISO, ISAF, Germanischer Lloyd and VO70 controls and designed so the boats will not only survive this round the world race, but the next one in three year’s time. This is fortunate, because if the Volvo crews can’t gain an advantage through their equipment, then they will do so of course via their sailing prowess and cunning, but particularly by pushing the &!$^£ off their boats, which are certain to be sailed with the volume constantly turned up to 11.

The boats are fitted with a load monitoring system, and there was some thought that this might be used to ensure crews didn’t push their boats too hard, which might impair warranty issues if they were to break. There was even talk of fitting an AC 72-style traffic light system in the cockpit to indicate when crews were pushing their boats into the red and the potential of their receiving penalties for doing so. But seriously?

As Abu Dhabi Ocean Racing Shore Manager Guy Barron points out: “It is a one design, so you shouldn’t be able to break it. The concern is that if it can’t be broken, then everyone is going to push it. So how hard do you push it? Until it breaks! So we’ll see them getting pushed harder and harder and we might even see them doing similar speeds, or more, than the 70s.”

The hull

Farr seems to have eased back on the substantial volume in the bow their last VO70 had, however perhaps to make up for this the VO65 features a reverse Dreadnought bow, reminding us of the first ABN AMRO VO70. The hard chine appears to be more pronounced than on Farr’s last VO70, now extending most of the way to the bow.

|

|

The 65’s maximum beam of 5.6m is only 100mm less than the VO70, making her relatively wider for her length, although still not as much as an IMOCA 60 (MACIF’s beam for example is 5.7m). We may be wrong, but there appears to be more rise in the deck going forward than the VO70s had.

Appendages

VO65s are fitted with the ‘standard’ package for canting keel racing yachts: canting keel (+/- 40deg canting angle), twin rudders and some giant asymmetric daggerboards, but these are conservative in their detail.

The rudders don’t kick up like many IMOCA 60s’ do, however there are – as was the case with the VO70 - an impressive number of redundancy systems in case of rudder damage. The boats carry an entire new blade and stock. This can either be inserted into the existing bearings or slotted into a cassette and hung off the transom, with a special connector that allows it to be hooked up to the principal steering mechanism or driven by its own tiller.

The draft of 4.78m is deeper than the VO70's 4.5 and the keel fin is forged with a composite fairing on its trailing edge. While IMOCA 60s are mostly fitted with a single hydraulic ram to cant the keel, the VO65 has two (like the VO70s). The rams are made of stainless steel – as going one design there’s is no need to use costly materials like titanium.

A welcome development is that the 65’s keel pin (the keel’s axis of rotation) is inclined fore and aft by 5° (something that Juan K tried on the first ABN AMRO VO70, before it was prohibited!) The advantages of inclining the keel pin is very complex, says Class Project Manager James Dadd: “The angle of attack of the bulb to the heeled waterflow is better so it creates less drag and the angle of the fin gives some lift with the result that the dynamic displacement is reduced, the amount of daggerboard needed is reduced and the drag is reduced. All the IMOCA 60s and Minis do it, so it’s nothing new. It was just banned in the VO70s as was a potential area for lots of expensive research...”

|

|

The boards, while immensely long and heavily overspeced, are toed out (ie they are close to vertical in the water when the boat is heeled), whereas the VO70s, in particular the Farr designs, had their boards more vertical in the boat causing them to be inclined when heeled, thereby providing a vertical component of lift (although to nothing like the degree of the heavily toed in boards, that protrude through the deck more or less at the gunnel, on IMOCA 60s like MACIF and Banque Populaire). One advantage of having ye olde school toed out boards located closer to the boat’s centreline is that they can be hoisted via a simpler (and cheaper) purchase system fitted up the mast.

On Abu Dhabi Ocean Racing they have been allowed to put special stoppers on their boards, something that will be duplicated on other boats. As Guy Barron explains: “People would just open the jammer in the pit, dropping the board and it would come smoking down.... So we changed our stops to four skateboard wheels.” These innovative stops also hit the bearing in the top of the daggerboard case rather than the deck.

While asymmetric, the boards can be end for ended and swapped over, in the event of one being damaged. The boards come complete with the fittings to do this, but, because of this, the boards can’t have the profiled bottoms we saw in the last generation VO70s that neatly close the aperture in the bottom of the daggerboard case.

An issue with some of the VO70s in the last race was that the boards were so long that the keel, when canted, could hit the end of them. This has obviously been rectified with the new VO65.

A neat new feature is that while sailing the crew can adjust the linkage between the rudders – carried out via a little wheel mounted on deck immediately ahead of the liferafts. This allows the balance of the boat to be tuned via a means other than the sails.

Cockpit

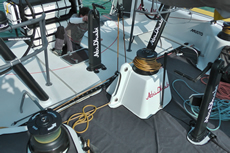

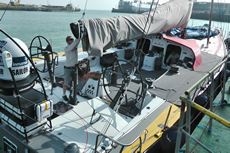

As mentioned, there are few surprises with the cockpit layout. There are the two helming stations immediately aft of the main sheet track that spans the full breadth of the cockpit sole. There is a separate pod for the main sheet winch immediately ahead of this with the hydraulic control panel on its aft side. The mainsheet reachs its winch via two turning blocks on the starboard side of the pod.

The winch package from Harken includes three pedestals, including one mounted aft, in front of a small hatch in the cockpit floor. In addition to the main sheet winch, primary and runner winches, there are three pit winches, the pit area divided in three, separated by the twin companionways. The companionway hatches are neatly housed in their own garages within the cabintop.

If the aft gantries were impressive on the VO70s, they are even more so on the VO65s, housing two liferafts as well as the substantial Inmarsat satcom domage and waterproof camera gear. Following the Rambler capsize we have previously wondered why it is not mandatory to have liferafts on canting keel boats fitted into recesses in the transom in case of keel loss and capsize, as is the case on the IMOCA 60s (although they have proved to do a relatively good job staying upright, even without a keel...) And we raise this again with the VO65s...

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

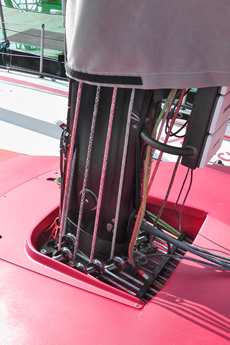

Rig

Southern Spars have provided the masts plus the EC6 carbon fibre standing rigging. However in another move towards the IMOCA class, the masts are now deck, rather than keel, stepped, with a slight sweep back on the three sets of spreaders. While this may limit some of the tuning that can be done to the mast, it does improve the watertight integrity of the deck with all the lines running back from the mast step to the pit through tunnels in the cabintop, again very IMOCA 60-like.

The runners and checkstays are fitted with hydraulic deflectors, enabling them to be pulled into the top of the mast at a lower position for when the main fractional J1 headsail is being used.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In addition to the runners and deflectors, the outhaul is also on a hydraulic ram as are the tacks for the J1, J2 and J3, countering the masthead locks these sails have.

Another feature on the VO65 to come from the IMOCA 60s, are the reaching struts/outriggers. These are poles protruding laterally to 1.5m outside of the deck perimeter to hold out the kite sheet, enabling deeper angles to be sailed downwind. There are two attachment points for these, one forward, one aft on each side of the boat.

|

|

|

Foredeck

At the pointy end, there is of course a bowsprit, which at 2.14m is again relatively longer for the length of the boat than the VO70 sprit (which was 2.15m maximum). The bowsprit is a bolt-on affair with two tack lines extending to its end (ie there’s no facility for tacking sails half-way along the sprit) and a single bobstay to counter luff loads from the kites. The tack lines run aft along the foredeck through tunnels that stand proud of the deck (doubling as footholds for the crew) and then back to the cockpit through tunnels in the sides of the cabin top.

A substantial rail runs around the perimeter of the foredeck just proud of the deck to which sail bags can be lashed. There is a moderate sized foredeck hatch.

|

|

|

Sails

The sail wardrobe, including the kites, is in North 3Di (Twaron aramid or Dyneema) and now comprises just 12 sails in total, of which eight can be carried on board at a time, with the extra four shipped as spares. This compares to the last VO70 wardrobe of 17 sails plus three storm sails.

The eight sails are: Main, J1 (upwind 8-15 knots and reaching), J2 (in 13-25 knots upwind or as a spinnaker staysail for the MH-O or A3), J3 (upwind 22-35 knots or as a genoa staysail for the J1 or FR-0), Cuben fibre A3 (120deg TWA or more), fractional Code 0 (FR-O – downwind and reaching, or light upwind), masthead Code 0 (MH-0 – reaching/downwind in light to moderate), plus a J4 storm jib (also used as a small staysail).

Bear in mind that these sails are all one design, built by North in batches and cannot be recut or tampered with by the teams. Once supplied, teams are obliged to paint their sails, in order that the weights of the sails remains consistent.

Teams get a suit of sails with their boat, and get another full set for the race, plus the four spares. According to Guy Barron one of the few areas teams can gain some differentiation over their opponents is on the choice of which spare sails they will order and this decision must be made early as these sails are to be ordered at the same time as the race suits.

In exceptional circumstances, such as a dismasting, a team will be allowed to use a sail from its original wardrobe. As Guy Barron puts it: “If you happen to lose one over the side, that wasn’t one of your back-ups then you have to come back to these sails. So you need to look after these sails from the word go.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Accommodation

Down below is cavernous compared to the VO70, partly due to the cabintop and the raised deck around the cockpit, that allows you to more or less stand up rather than crawl while going aft. However the substantial nature of the bulkheads means it will be harder to shift the stack fore and aft.

The finish throughout is excellent and the builders have done a top job in this respect as has James Dadd in ensuring the integrity of the one design. To date the 12,500kg VO65s have all come out within 30-40kg (or around 0.3%...). “When you think what they have all gone through, that is amazing really,” says Barron. “I know that Greens worked hard at having the same people doing the same jobs...”

In the main ‘saloon’ area there is the galley slung off the aft side of the main bulkhead, complete with a stove and modest sink to port and starboard and galley stowage in bags slung off the bulkhead. The cooker on Abu Dhabi Ocean Racing apparently is a replacement for the twin jet boilers fitted on earlier VO65s, which in a seaway had a tendency to capsize their load when the whole crew was being catered for.

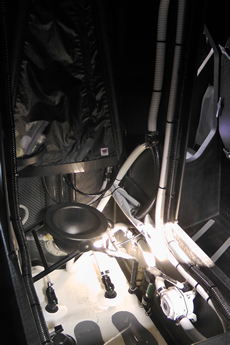

The galley hovers over the scary wet box for the canting keel where there are three inspection hatches to check there is nothing untoward taking place with the giant Cariboni-supplied rams and their attachment to the keelhead.

The engine (a Volvo, of course) is fitted immediately below the companionway, which makes it a little awkward getting below if it is being worked on. With their past experience of VO70s, what to hang off the front of the engine is now highly refined and on the VO65 there are two substantial alternators, plus a hydraulic pump to drive the keel rams. These rams can also be driven electronically if required and in dire emergency there is also a manual back-up pump – the same arrangement as the VO70s.

There are of course sturdy pipecots outboard on either side of the boat from the main ‘saloon’ area, aft. Beneath the cockpit, as on the VO70s is the navigation station where there are two tackable seats, with the nav instrument panel able to rotate, so those working here can always be to windward. The one design nature of the boats is such that even the laptops used on board are standardised.

Aft of the V-shaped bulkhead beneath the main sheet track, is the station for the media crewman, complete with all the comms gear.

|

|

|

|

|

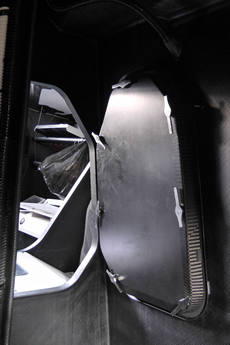

Going further aft this is another bulkhead with an aperture in it through to the stern compartment containing the wing tanks for the water ballast and the steering, including the two stocks and quadrants and their adjustable linkage mechanism. There is also an escape hatch through the transom.

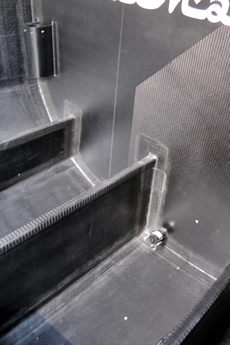

In the opposite direction, passing through the main bulkhead we stopped to stroke the watertight doors, immaculately manufactured in carbon fibre, composite works of art, but also highly robust looking. The compartments within the VO65 have through-bulkhead plumbing ready installed in the event of taking on water, when compartments can be drained by a bilge pump or in the case of holing, by a pump on the main engine.

On the forward side of the main bulkhead is the carbon fibre gimballed head. Running up the centreline of this compartment is the forward ballast tank fitted between the central two of the four monster 2ft deep longitudinal stringers. Either side are the daggerboard cases with one of the permitted stacking areas on the weather side of these.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On the forward bulkhead are two of the four weight corrector stations (the two others are aft). As mentioned there is impressively little difference in weight between the VO65s built to date and in allocating the weight correction for each boat the measurers are not only looking at the boat’s overall displacement but also how it balances, so they can install weight correctors to even this out.

Movable ballast

Compared to the VO70s, which only carried a single centreline water ballast tank aft, containing 1.6 tonnes, the VO65s have 800lt (ie 800kg) wingtanks in the aft quarters – but also are fitted with a single centreline tank (albeit with a baffle) forward containing 1.1 tonnes and used typically when sailing upwind.

The aft wing tanks can be filled via a scoop or by pump and water can be transferred between the tanks by gravity or pumped up to weather if a quick tack needs to be put in (when it takes around six minutes to fill the new weather tank). The scoop is turned in the opposite direction to empty the tanks.

Stacking

The stacking rules remains similar but are more refined than was imposed on the VO70s last time. The stack is obviously smaller with less sails to be moved around. And more is tacked down: all safety kit for example – such as anchors, warps, chain, flares, lifejackets, medical kit, etc - is now sealed in a specific position where it must remain unless it is to be used in anger. And there are set places where the stack can be moved down below, such as outboard of the daggerboard cases and for example there is no stacking on the bunks, which is now solely the domain of crew and their personal equipment.

A grey area is spares and this is another of the few areas where there is can be differences between the boats, with teams allowed to choose what they can carry, at the expense of course, of its extra weight. Are these spares be stackable? Guy Barron comments: “If you wanted to take an spare alternator and it wasn’t part of what Volvo agreed, they would weigh it, they would decide whether it was stackable and they’d probably say ‘no, it’s not’ and it would get sealed in position.”

But perhaps teams will figure that carrying extra weight is good? As Barron puts it – do you take tools made of lead or titanium?

Normally at this stage of the Volvo Ocean Race cycle teams are busy refining their sail wardrobe, shedding weight wherever possible and attempting to eek out every fraction of a knot of performance. This time round with their new one designs, crews are busy familiarising themselves with their new craft, while trying to ensure they are getting the maximum from the immovable package. But they are also attempting to find all the loop holes they can in the rule and one hopes that Volvo is staying one step ahead of the game in this respect.

Latest Comments

Add a comment - Members log in