Life on board at 40 knots

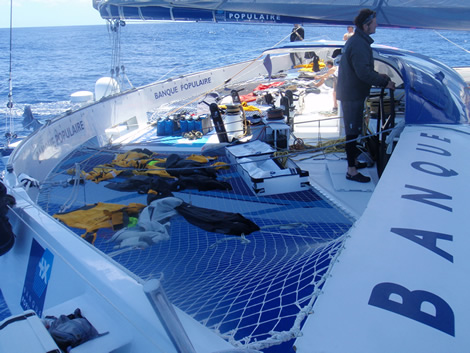

Getting around the world non-stop in record time on a boat that can hit 48 knots, has a 35 knot cruising speed and is a colossus - at 40m long by 33m wide, with a 47m tall wingmast and a mainsail more than 2.5x the size of a VO70’s - is no mean feat. On board the Banque Populaire maxi-trimaran the crew looked like ants.

For Brian Thompson, the sole Brit among the Jules Verne Trophy winning crew, this was his fourth lap of the planet and his third on a maxi-multihull, his two previous experiences having been with the late Steve Fossett on their non-stop lap aboard Cheyenne and then in the Oryx Quest as skipper of the winning Doha 2006.

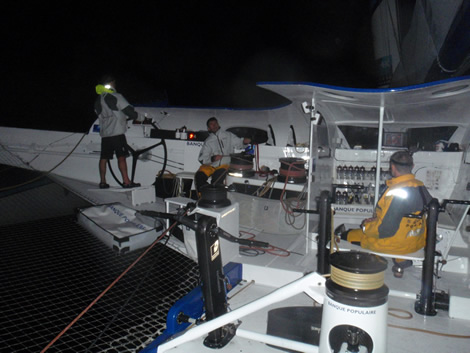

According to Thompson there was a real routine to their life aboard during their 45 days at sea during the Jules Verne Trophy. With 14 crew on board they ran three four man watches with navigator Juan Vila and skipper Loick Peyron out of the watch system.

Thompson was on watch with watch leader Yvan Ravussin (the elder and less crazy brother of Race for Water MOD70 skipper Steve), former Figaro sailor Thierry Chabagny and ex-Mini sailor Pierre-Yves Moreau.

Their watch was from 0800-1200 UTC both in the morning and in the evening and would be followed by four hours off and another four on standby. Off watch was when they would get some food and sleep in their bunks, while on standby watch they would have their foulweather bottoms and boots on. “You might spend the first two hours doing some jobs around the boat and then maybe the second hour and a half before you have got to go on watch you’d get some shut eye unless you were cooking a meal,” recounts Thompson of their stand-by watch.

While the watch times remained on the allocated times UTC for the duration of their voyage, meal times - typically at 0800 in the morning and evening - did shift as they went around the world. “Because you are going east and going towards the sunrise, the days are getting shorter and suddenly dinner is in the middle of the night. So every few days you’d switch it back four hours.”

The standby watch would cook. As to the food, this being a French boat, it was not simply the usual freeze dried mulch with a bit of Tabasco added for good measure. “We had some fresh pasta which was a big treat. We had some chicken from Fusion, the company in Portsmouth, and we’d rehydrate that and put that in with the fresh pasta and have a sauce and that was really good, a great meal. We had lots of different types of food. We had some Swiss Michelin chefs making some of our sauces and things. To be honest by the end some people were tired of it and just ate porridge and noodles, but the French do have a finer palette.”

While Banque Populaire is 40m long, and you might think this offers the opportunity for some spacious accommodation, it is still a racing trimaran and down below the crew live in a narrow tube with the living area extending only as far forward as the daggerboard case. in terms of cubic area it is probably smaller than a Volvo 70.

The crew on watches shared four pipecots in a single tier towards the centre of the boat, forward of the galley. “I was in the top bunk, 8ft off the ground so you had to climb up the others which would be quite dangerous," says Thompson. "Climbing in and out in rough conditions was quite tricky too. So I shared that with two other people (on other watches). You have your own sleeping bag and I used to use my jacket as a pillow. It was well organised with the stowage for the sleeping bag and your gear.”

In terms of personal gear there wasn’t much, a few people took books and almost everyone had an iPhone or an iPod, hooked up to the on board WiFi. “That really made a difference because people could check their mail whenever they wanted in their bunks. And we had a computer which had some movies on. A lot of people watched a little bit of a movie on their off-watch but I didn’t watch movies and I didn’t really listen to music after the first two weeks.”

While down below was a little cramped, the equivalent of the ‘saloon’ area was the large doghouse on deck, surrounding the companionway with bench seating down either side.

“With any sail change or even moving the daggerboard or the foil, you’d be called up on deck," says Thompson of the stand-by. "Often you’d split it into some work and some sleep, because often in your off-watch you only sleep for two hours because you eat and you check your mail and you might be called for a sail change. You get a lot more sleep than in the Vendee for sure.” Thompson reckons that typically you might get three hours sleep a day in the Vendee Globe whereas on Banque Populaire it was more like six. “In this you are concentrating much harder than in the Vendee in terms of driving. If you weren’t rested you wouldn’t be able to do it, because it is a powerful beast...”

On watch

Those in Thompson's watch drove for an hour each but they then shortened each stint to 40 minutes, which Thompson says worked much better.

If you consider images you see of green water rolling aft down the deck of Volvo 70s - now imagine how fast the water is flying aft on a boat that is typically going 50-100% faster and has wave piercing bows. Fortunately there are advantages to a boat being 40m/140ft long in that the bow is further away, but even so when it is travelling at 40 knots there remains the potential for serious crew injury if they are caught by the water blasting across the deck.

So to protect the crew from the worst of the air borne spray, along the top of the aft beam, forming the forward side of the elliptical cockpit, there is a robust protective cowling.

“The protection is incredible in the cockpit, because it is always wet with spray coming off the bow,” says Thompson. “I was trying to work out exactly where it comes from... The boat doesn’t often fly a hull, but it is almost flying a hull and because it has a lot of rocker it goes up and down, a bit like an accordion. Each time the forefoot gets more immersed, spray flies back and cuts into the front beam and some of it flies just past the starboard pod and some down the port side. If it is a bigger wave that smashes down it will widen out and hit the helmsman. I got hit by one the other day which knocked me backwards. I have never been hit by a wave quite that big. On Cheyenne I remember Nick Leggatt [now competing in the Global Ocean Race] got hit by a wave on the side of his head and he slammed it into the compass and he’s got a big cut in his cheek still.”

The cockpit cowling provided protection up to chest level for towering Thompson (head level for everyone else) but there was an addition windscreen on top of the cowling on each side of the cockpit around the helm's position. However these were both flattened by waves.

“The cowling is brilliant and all the winches are behind there, so you can be to leeward and you’ll be crouched down and all the water is just going horizontally overhead and you can look up at the jib trim.”

Even with the cowling around the cockpit and additional windscreen, at speed there was still too much spray for the helmsman. “I ended up using one of those Gath surf helmets a lot because although the visibility is a tiny bit less, but you are not squinting all the time. You can steer a little bit better overall and you are a lot less tired at the end of it and if you are going to do that day after day...”

The helmsmen obviously had different styles and Thompson said he learned from Yvan Ravussin. “It was very interesting to sail with Yvan because he has only ever sailed multihulls - all the Swiss lake boats - and he is very much about balancing the helm, so the helm is absolutely neutral, then it becomes easier to drive because you are not forcing it down or up all the time. So a bit different to a monohull where you have some helm on.”

Thompson says that on Banque Populaire you have you be quite precise helming because there is a fine line between going too high or too low and the speed either plummeting or overpowering the boat and causing the hull to fly. “You have to be much more accurate than on a monohull in terms of steering because either way something dramatic will happen. There is probably a 10° margin you have to sail within, but generally you try to get it down to a 3-4° margin. In day time with good visibility it might be 1°.

“And you definitely play the waves, some more than others. I do it quite a lot, especially downwind to get a little more VMG - go down, but come up before you lose speed.”

With wave piercing bows, giant very long bows and the rig a long way aft, they never planted Banque Populaire as we used to see on the ORMA 60s which could bury up the front beam when pressed. For Thompson the experience was uncomparible to the previous catamarans he circumnavigated aboard. “Nothing like a Cheyenne plant or an Ollier cat plant where there was a front beam and it was very abrupt,” recalls Thompson. “It was more the bow being planted causing a lot of drag.” As a result Thompson says they never felt that concerned about the possibility of pitchpoling.

While following them from on land it appeared that at times they were adhering to speed limits, in fact Thompson it was more relaxed and that, the call being more one of ‘just cool it’ rather than ’sail 34 knots’.

“We had a northerly gale [just coming up to New Zealand] and we definitely backed off on that. It was unbelievable rough. And you just don’t really know where the limit is, because most of us have sailed on multihulls that have broken and you think will never break until they break. This one isn’t any different – you can break it, but you are sort of judging it by what the human body will take. There were times in that northerly gale when I was holding a coffee mug and if I took the lid off the liquid just flew out vertically. So that was quite a lot of G-force...”

Whenever they were at pace and the crew had to go forwards they would slow the boat down. “It can be six of you going forward for some big manoeuvres like changing gennikers. Then they will slow down for that, so you get a little bit wet, but not soaked. They might go 8-10 knots slower – so 22 instead of 34...but that is not too bad. And often you are dragging the big heavy sail bags around the net. The big genniker is around 400kg when it full of water.”

In addition to the mainsail Banque Populaire carries a storm jib, staysail, Solent jib and three different sizes of genniker – all on furlers. They were made by Incidences in cuben fibre and the crew were fortunate to have Jean-Baptiste le Vaillant from the Incidences loft in La Rochelle in their number – previous le Vaillant has a regular in Loick Peyron’s crews and was one of the few crew to come on board after Peyron took over from Pascal Bidegorry as skipper last year.

The sails get stacked fore and aft but they don’t get put it up on the windward float because then the righting moment would get too much for the structure, Thompson maintains. “Downwind you put them both back – one to windward and one to leeward and that way you are also protecting the leeward back beam with the sail bag.”

Typically downwind they reefed in around 24 knots (or 22 if the big genniker is up) and go to the second reef at 27-30 knots and down to the deep third reef at 36-37 knots.

Sail changes were anticipated a long way in advance and this allowed them usually to be carried out at watch changes when there were naturally more people on deck to do the handover, with eight in the watches plus Peyron and Juan Vila. However according to the conditions the whole crew could be called upon for major changes like peeling between two gennikers. “You have to roll up the staysail, roll out the solent, roll up the genniker, drop it, put up the other one, unfurl it. So we never did bear headed changes.”

During the 45 day voyage Thompson says there were only a couple of ‘all hands on deck moments’...“when furlers broke and a genniker ended up flying in the air. We had that a couple of times when I had to go and grab the furler. Then we had to rebuild the furler.”

Thanks to the caution and experience of the crew, Banque Populaire experienced almost no significant technical problems aside from this on their way around.

“On Cheyenne we had to go up the mast 80 times with the mast track coming out and things like that,” recalls Thompson. “There was a lot of drilling going on. On Doha [the former Club Med] we had nothing to do to that boat. Dalts did a good jobs sorting her out. It was bulletproof."

From here Thompson is continuing to look for sponsorship for next year's Vendee Globe.

Latest Comments

Add a comment - Members log in