Groupama 3's long way around

There are a few sore heads in Brest this morning, following Groupama 3 setting a new Jules Verne Trophy record time of 48 days 7 hours and 44 minutes on Saturday night, their triumphant arrival back into the northwest France port yesterday morning and the substantial party laid on for the team at the Incidences loft last night.

One of the proudest to have been part of Franck Cammas’ team on this historic Jules Verne Trophy record is her American navigator, Stan Honey. Honey is famous for having sailed on ABN AMRO One when it won the 2005-6 Volvo Ocean Race, but before that was also Steve Fossett’s principle navigator on PlayStation/Cheyenne.

This occasion was Honey’s fourth stab at sailing round the world non-stop on a big multihull. He was on board PlayStation for The Race in 2001, (when they were forced to retire). For Fossett’s non-stop round the world record, the start date drifted on too much and Honey had to miss it due to Pyewacket commitments, handing over to Adrienne Cahalan. Then finally there was Groupama 3’s aborted attempt last autumn.

An unusual feature of the Groupama and Banque Populaire maxi-trimaran crew line-ups is that the only non-French on board (or Franco-Swiss) are the navigators - Pascal Bidegorry having Marcel van Trieste in that spot.

Honey is a little hesitant as to why this might be: “It could be because the approach Marcel and I use for navigation is a very intensive one - we both come from a Volvo background where the assumption is that you exhaustively optimise, whereas the French approach, because of their background in shorthanded sailing, they have to take more of a triage approach to it, where you come up with a really good answer with a small percentage of the effort because they are not able to work the problem full time the way I’m used to as a full time navigator on an offshore racing boat or a Volvo boat.”

So how did he find sailing with a French crew? “It was much more fun and interesting than I could have imagined. Part of that is just because the French offshore sailing scene is this closed book to most of us. It is a kind of insular, isolated community, and of course we all have huge respect for it, but we don’t have a lot of visibility into it. So I was delighted and surprised to get the call, because God knows there are lots of skilled offshore navigators in France - in fact I think almost every French sailor is a skilled offshore navigator, because they grow up singlehanding! But it was an irresistible opportunity, because the French are the best at offshore multihulls and Groupama is among the best of the teams.”

He was tracked down by the team about a year ago, after their boat had been repaired following its catastrophic breakage conveniently close to the coast of New Zealand in 2008. The aim was an attempt on the west to east transatlantic record followed by the Jules Verne Trophy.

“We did a ton of sailing in preparation,” recalls Honey. “We did the transatlantic record. I joined the boat for several sessions in France and for a trip from Lorient all the way to Istanbul and from Valencia back to Lorient. I also spent a week in Toulouse at Meteo France working with Sylvian [Mondon – the team’s shore-based weather forecaster and router].” Honey, and the project as a whole, benefitted hugely from being able to draw on the strength of the French met office and their giant resources.

While Honey has been fortunate enough to have sailed on many of the world’s top race boats, he admits an attraction to the G-Class maxi-multihulls, especially the new generation such as Groupama 3 and Banque Populaire. “Playstation was an enormous innovation for her time, but she was a big grunty strong heavy boat and it was a handful to steer and a handful to sail and to crew on. The impression you get from a boat like Groupama is just finesse and elegance. And obviously there is a lot of stability there and it is a big boat, but it is just really light on the helm and beautifully rigged and everything works perfectly and nothing is too hard to do. So it is hard not to love the boat as a sail boat.”

Compared to ABN AMRO One, the challenge navigating Groupama was very different. Honey says that the Volvo Open 70s are designed to be good all-rounders but with large multihulls such as their 105ft trimaran, the performance is considerably less even. Groupama 3 is particularly quick in light conditions down to 7-8 knots, but conversely the crew throttles right back to preserve the boat as soon as the sea state gets up, at a time when a Volvo team would just grunt up and take it on the chin.

Thanks to the outrageous speeds capable by a boat like Groupama 3 the technique is simply to sail around places where progess might be slow, even if the downside is sailing many more miles.

Therefore, more than on any previous voyages he has done, Honey spent much time this trip examining sea states with the help of his Meteo France colleague. “Not just combined sea, but also you separately look at the swell and at the wind waves and in some cases you look at two sets of swells. Then you look at the direction and the period and sometimes the differences are very subtle, meaning you will look at a sea state, and you will think ‘my God, this is going to be horrible, after this cold front’, but then you are surprised because it is just long enough where the boat can smoothly pitch through it, whereas if it is just a little bit shorter, you are in a situation where the boat is going to start slamming and you are going to start throttling back.”

This, Honey says, was when the resource at Meteo France especially paid, allowing them to get accurate sea state data which they could incorporate into the boat’s polar using the French Adrena navigation software they were running.

The voyage

Generally looking at her Jules Verne Trophy attempt, Groupama 3 was less lucky with the weather than other previous attempts have been, for this, alongside not breaking the boat, and probably ahead of boat performance, is today an absolutely vital ingredient to a record breaking non-stop circumnavigation.

The weather of course is in the lap of the Gods and it is down to the crew and the navigator to make the best of it, with the exception of the start when it is the role of the navigator and the met team to pick a good departure window. While weather model runs look up to 15 days ahead, typically the only data accurate enough for oceanic record attempts is eight days ahead, but on the Jules Verne this is enough to get a boat well into the South Atlantic.

Groupama 3 set sail on 31 January in what Honey says was a marginal departure window. Typically over a winter in northern Europe there are four or five of these. This year, they fell on 5 November (their first attempt this winter), on 5 December and 5 January, 31 January and 8 March. So this year Honey says there were four and a half, the half being 31 January, however he points out that it was essential that they bagged the Jules Verne this winter, so they were forced to leave, despite the forecast oscillating between “acceptably good and horrible”.

“If that had been a fall [autumn] window, we probably wouldn’t have gone because of the risk of the South Atlantic going bad, but it was a much later window so we went for it because it was our last shot. Then the South Atlantic went bad on us...”

Conversely on their 5 November departure they had good weather outbound down the full height of the Atlantic and Honey says the Indian Ocean was lining up well too.

Thanks to the activity of the St Helena high they were badly caught in light winds in the South Atlantic but once into the Indian Ocean the pace picked up and Groupama 3 claimed the record for this part of the course.

Aside from the South Atlantic, the Pacific crossing, Honey says was perhaps their biggest disappointment. Early on it looked like they might reach Cape Horn one and a half days ahead of Orange 2’s 2005 record pace. Unfortunately on the approach Horn a fast moving depression was overtaking them from the west and they little option than head dramatically north to sail around the top of it.

The speed of maxi-multihulls such as Groupama 3 makes them capable of sailing at a similar speed to the southeasterly or ESEerly track of depressions as they move across the Southern Ocean. Thus in ideal circumstances a boat can ride as few as two depressions that will take them the distance around the bottom of the planet.

Honey explains what happened before the Horn: “The thing that went wrong for us in the Pacific was that the upper level flow went zonal, meaning that the jet stream didn’t have the big ridges and troughs in it, so then the systems started moving straight west to east and fast - too fast for us. We had a great ride in the Indian Ocean when we finally caught that system and we had some great rides in the western part of the Pacific, but by the time we got to the eastern part of the Pacific the system had gone zonal at the upper level and the low behind us was too fast for us to stay ahead of.”

This was why they had to make a sharp left hand turn and head north, for as Honey warns: “The one thing that you don’t want to do in the Southern Ocean is to get south of a low – I think ENZA showed that to everyone. Once you are down there you are in a world of hurt and it is very difficult to get back north. So our choice on that system, was that we had to get around the Horn in front of it or we had to follow it round. One of the tough decisions of the trip was the final realisation that we weren’t going to stay ahead of that thing.”

And yet despite this major detour, Groupama 3's time for the Pacific crossing was only an hour short of the record. “We really could’t be too disappointed. It could have been a legendary Pacific run, if we’d managed to stay ahead of that low or if it had been a little slower.”

Coming back up, the South Atlantic once again proved unlucky, but on this occasion thanks headwinds as well as light winds, but as Honey points out “the thing that saved us is that Groupama is very nimble and very very good in the light, so even though we had some horrible light air right on the nose stuff, the boat really performs well in that stuff. You go upwind at 20 knots and if there is detectible breeze you are doing 15. It is a really cool boat.”

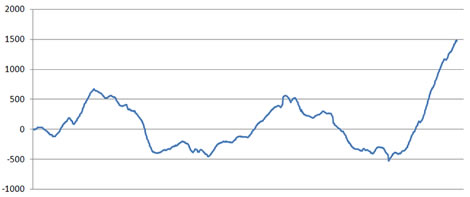

With just the North Atlantic to go, Groupama 3 crossed the Equator with a 400 mile deficit on Orange 2 and for on-lookers their chances seemed at this stage to be in the balance. However with the forecasters view Honey says they weren’t too worried.

“From the time we were about at Montevideo, or even at the Horn, looking at the weather I had a hunch we’d be in pretty good shape for the North Atlantic, because long term pattern there was very good . The other thing was that Orange had extraordinary bad luck in the North Atlantic on the way home. Part of that may have been that Bruno had the record nailed, and he may have been sailing conservatively - that was something that Steve Fossett always used to do too - once we had a record in the bag he’d back way off. But in any event there were several slow times where Orange basically stopped for a day or so in the north Atlantic, which were also going to make us look better.”

Above: Graph showing how Groupama 3's progress against Orange 2 wildly fluctuated (miles +/- up the LH side)

From being 400 miles behind at the Equator, the crew of the green trimaran turned their fortunes around and completed the course on Saturday night with a lead over Orange 2 of approaching 1,500 miles or 2 days 8 hours and 35 minutes faster than the previous record.

Given better conditions Honey reckons they could have shaved three or four more days off this, whereas Banque Populaire, could, if they were fortunate, didn’t break anything and actually left, take five days off – so round the world in 43 days... For if the transatlantic record is a benchmark, Banque Populaire is the faster boat. But Honey wonders if that would have been the case on this record. “We really did have to rely on the boat’s distinctive capabilities in the light, mealy stuff and in that it might well be that Groupama is just as good or maybe a tick better than Banque Populaire. When you get into downwind, fetching in front of a system in flat water, that’s the hot ticket for her. That is of course what we both had for the transatlantic.”

Groupama 3’s Jules Verne Trophy record was despite her sailing an enormous course of around 28,523 miles. The World Sailing Speed Record Council’s official distance for the Jules Verne, which presumably is as direct as landmasses allow, for example is just 21,760 miles.

Aside from major meteological hurdles such as the Atlantic high pressure systems, maxi-multihulls also typically take a route much further to the north than they did in previous years. In theory the most southerly they have to go is Cape Horn at around 56degS. Back in 1994 when she broke the record, ENZA New Zealand plummeted all the way down to 62deg09, while three years later Olivier de Kersauson aboard Sport Elec made it down to within a few miles of 60degS. In comparison Orange 2 had a momentary spell at 57degS, while Groupama was briefly down at 58deg before hightailing it north to get around the depression approaching the Horn.

“I think you’ll see more of that as people who do the same numbers that we do, realise that if you get the conditions you want, the boats are just SO much faster. It just doesn’t pay to take the Volvo approach and say ‘okay guys. Grunt up, we’re going through it’. Plus you have got the risk of breaking the boat. And as the boats get higher performance and as you see boats taking more advantage of foils [he refers to L’Hydroptere Maxi], I think you will see boats being willing to sail all over the ocean to get the conditions they want. Because if you get the conditions you want, you are so fast that the extra distance doesn’t make any difference.”

So if Groupama 3 took detouring to a new level, expect to see this a whole lot more in the future.

For the Groupama 3 crew arriving at the finish line there was a huge collective sigh of relief as achieving a new Jules Verne Trophy record time was the culmination of a five plus year program. This had included the launch of the boat in June 2006, a west to east transatlantic and 24 hour record in 2007, a Jules Verne Trophy attempt in 2008 that came to an abrupt end and the near loss of the boat, the rebuild of the boat throughout that year and being beaten across the Atlantic last year in emphatic style by the newer and 20ft larger Banque Populaire. So for the Jules Verne Trophy, it was third time lucky.

Honey says they didn’t break anything major this time – a couple of mainsheet blocks and some chafe – and the boats finished in 100% fighting trim. Aside from a keen maintenance schedule, this was also a side-effect of the safer route they took.

Day to day, Groupama 3 ran three watches with the stand-by going up on deck for manoeuvres and sail changes/reefs/unreefs and Honey going to help. “My life was structured around six forecasts a day and trying to get a nap between a couple of those and then for every event on deck no matter how small, I’d get pulled up along with the stand-by watch. Then I’d definitely get on deck every watch to see the sky and the water and to brief the watch captain and so forth. And when I was on deck, the guys would always try to pass the helm off to me and rope me into it. I appreciated that. Of course I would drive now and again, but the boat has some of the best multihull helmsmen on the planet and I wasn’t going to improve the performance by steering and I am the only navigator. My responsibility was to make sure that I didn’t overlook anything on the routing, so guilt would strike pretty quickly and I’d get down to my office again.”

Despite only seeing 40 knots of wind at the top end of a squall, the peak boat speeds during the trip were around 45 knots. “We had a few 40 knot sessions of boat speed, which we weren’t really looking for, but in flat water it was fine. There were times when conditions were quite stable when we’d be flying the centre hull off and on – that wasn’t the goal, but nevertheless the guys couldn’t resist it, when the conditions were really nice. We had some of that on the last day coming in on the beautiful northwester - Thomas [Coville] and Franck [Cammas] were flying the centre hull now and again. That was fun. We never had any hair raising situations and most of that was because we sailed around them.”

The future

From here Honey says he hasn’t committed to any big program. There is presumably the offer to go with his new friends on a green 70 footer in the next Volvo Ocean Race, but Honey says he has won that race already. He is also uncertain whether he is ready to take more of a shore-based job with a Cup team. “And Sally [his wife] wants to go cruising, so it might be time to do that.”

The only thing he has signed up for to date is doing some races on Alex Jackson’s newly rejuvenated super-maxi, Speedboat for the Bermuda Race followed, possibly, but another attempt on the monohull transatlantic record.

So finally - what will Honey be telling his future grandchildren about this record? “One of the parts that is interesting for me, growing up as a kid, was reading about the 24 hour records of the Clipper ships so it is fun to have been a part of that, to have participated in one of those records, Lightning and Sovereign of the Seas are in the same category. It is also fun to have an opportunity to participate in the French offshore scene, which is something I’ve read about and marvelled at.”

Tick in the box.

Previous Jules Verne Trophy attempts

| Date | Boat | Type | Skipper | Time |

| 1993 | Charal | 27m van Peteghem Prevost tri | Olivier de Kersauson | Retired day 23 after collision |

| 1993 | ENZA New Zealand | 26m Irens catamaran | Peter Blake/Robin Knox-Johnston | Retired day 27 after collision |

| 1993 | Commodore Explorer | 26m Ollier catamaran | Bruno Peyron | 79 days 6 hours 15 minutes 56 seconds |

| 1994 | ENZA New Zealand | 26m Irens catamaran | Peter Blake/Robin Knox-Johnston | 74 days 22 hourr 17 minutes 22 seconds |

| 1994 | Lyonnaise des Eaux Dumas | 27m van Peteghem Prevost tri | Olivier de Kersauson | Too slow. Finished in 77 days 2 hours |

| 1996 | Sport Elec | 27m van Peteghem Prevost tri | Olivier de Kersauson | Too slow. Abandoned |

| 1997 | Sport Elec | 27m van Peteghem Prevost tri | Olivier de Kersauson | 71 days 14 hours 22 minutes 8 seconds |

| 1998 | Royal & SunAlliance | 26m Irens catamaran | Tracy Edwards | Dismasted on day 43 |

| 2002 | Geronimo | 34m van Peteghem Prevost tri | Olivier de Kersauson | Retired day 11 with steering problems |

| 2002 | Orange 1 | 33m Ollier catamaran | Bruno Peyron | Retired after 30 minutes with broken mast top |

| 2002 | Orange 1 | 33m Ollier catamaran | Bruno Peyron | 64 days 8 hour 37 minutes 24 seconds |

| 2003 | Geronimo | 34m van Peteghem Prevost tri | Olivier de Kersauson | Too slow. Finished in 68 days 1 hours 58 minutes 02 seconds |

| 2003 | Kingfisher II | 33m Ollier catamaran | Ellen MacArthur | Dismasted day 26 |

| 2004 | Orange II | 36.8m Ollier catamaran | Bruno Peyron | Retired twice following broken crash box and then prop shaft fairing |

| 2004 | Geronimo | 34m van Peteghem Prevost tri | Olivier de Kersauson | Retired day 12 with broken genniker |

| 2004 | Cheyenne | 38m Morrelli Melvin cat | Steve Fossett | 58 days, 9 hours, 32 mins and 45secs* |

| 2004 | Geronimo | 34m van Peteghem Prevost tri | Olivier de Kersauson | 63 days, 13 hours, 59 minutes and 46 seconds* |

| 2005 | Orange II | 36.8m Ollier catamaran | Bruno Peyron | 50 days 16 hours, 20 minutes and 4 seconds |

| 2008 | Groupama 3 | 32m VPLP tri | Franck Cammas | Hull snapped off New Zealand |

| 2009 | Groupama 3 | 32m VPLP tri | Franck Cammas | Structural issue in South Atlantic |

| 2010 | Groupama 3 | 32m VPLP tri | Franck Cammas | 48 days 7 hours and 44 minutes |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Latest Comments

Add a comment - Members log in