What next for the Volvo Ocean Race?

Volvo Ocean Race CEO Knut Frostad was very much enjoying the new Brazilian stopover port when we spoke to him. In Itajaí, he said there was huge interest in the race, on a par with New Zealand, local enthusiasm no doubt boosted by Brasil 1’s participation in the 2005-6 race, followed by local hero Torben Grael winning the last Volvo Ocean Race as skipper of Ericsson 4. Some of his old guard – notably Joca Signorini and Horatio Carabelli now with the leading Telefonica team.

But underlying this, Frostad is concerned about the level of carnage that the fully crewed round the world race, he once competed in and now runs, has experienced this time around. “Obviously we are not happy with such a big part of the fleet is not able to complete a leg without stopping or retiring. That is no secret,” he says of the leg 5 outcome. Recently he issued a statement to this effect.

After leg five saw one dismasting, two cases of delamination/core shear, one ring frame failure and a broken rudder, following on from two boats dismasting on leg one when two had to be shipped to from Spain to Cape Town, Frostad says he has been following the accusations in the media that VO70s aren’t seaworthy enough. He is pleased at least that people care.

Frostad reiterates, as we have highlighted recently, that to understand the failures that have occurred it is necessary to separate the rig failures from the issues some boats have suffered with their hull's structure. To date this Volvo Ocean Race has seen three dismastings (Abu Dhabi Ocean Racing, Puma and Groupama) and one critical rigging failure (Team Sanya), but as Frostad points out it is the first time the event has had a rig loss since Brasil 1 on the second leg of the 2005-6 race (when Torben Grael’s VO70 had to be transported overland across the breadth of Australia to reach the Melbourne stopover).

“Obviously having finished the last race with all the boats having their rigs intact – we didn’t envision that we were going to have a problem in this area this time,” Frostad says.

Looking at the rig issues individually, Frostad points out they are also not related. “I have seen some commentary that carbon standing rigging is a fault, but we had carbon standing rigging in the last race and we didn’t experience the same problems with it then.” And they haven’t changed the VO70 rule to allow the standing rigging to be any less man enough for the task – the only alteration in current version of the rule was the addition of 10.16.3 requiring that rigging be nominally circular in section. According to Frostad this was to prohibit the use of very thin aerofoil-section carbon fibre rigging.

Abu Dhabi Ocean Racing’s dismasting on leg one and Team Sanya’s rigging issue on leg one is believed to have been due to a problem with the carbon cables not performing as expected in compression (ie when they were slack to leeward). On Puma the dismasting is believed to have been due a fitting that failed, and rumour has it that this fitting may have been manufactured from the wrong material. Meanwhile Groupama’s dismasting on leg five is still being investigated.

“I am disappointed with the rig problems,” admits Frostad. “That is a problem we shouldn’t have. The VO70 rule has had a very conservative spec for the rig. Ask any rig designer about the safety factors for a VO70 rig compared to one say the IMOCA class has and it is night and day. Our masts are over strength, but if there is a weak link then it is with the standing rigging.”

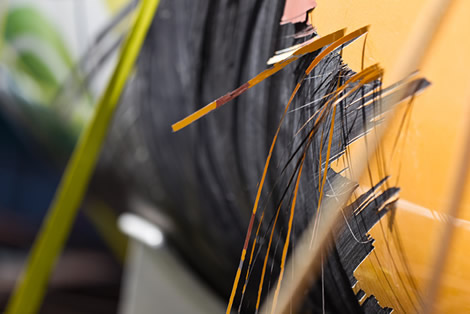

Three of the four rigging failures have been on boats using the latest types of ‘solid’ carbon fibre standing rigging, as supplied by Future Fibres or CarboLink, as opposed to the ‘soft’ alternative from Southern used on Telefonica for example.

“One of the big challenges when you have a total rig with hard carbon standing rigging is that it is difficult to pick up what failed,” says Frostad. “On Brasil 1, it was easy – all the standing rigging was intact – that was PBO. We could find the fitting that broke – which was a turnbuckle rigging screw.”

Equally the three structural problems that occurred in the hulls on leg five affected different parts of the boat. In Abu Dhabi Ocean Racing it was the chine on the port side, while on Telefonica it was in the middle of the boat between the longitudinals – in both these instances there was delamination and core shear. While on Camper it was a ring frame in the mid-bow that broke and this was nipped in the bud before delamination or core shear issues occurred in the hull.

All three of these instances may have been started off with the boats launching off waves into the severe upwind conditions as they left Auckland, but they manifested themselves as the boats negotiated the extremely confused seas as they approached the last ice waypoint in the Southern Ocean section of the Pacific. This was significant as at the time the boats were to the west of a front, where typically the sea state is extremely confused thanks to the wind having swung through 90 degrees, making this potentially rogue wave territory. Due to the speeds they were able to make, combined with the pace the front was moving east, the boats spent a prolonged amount of time in these conditions (much more than they have done in recent races).

As an aside, it was interesting to see the differing ways Telefonica and Camper dealt with their respective problems (having restarted leg five late, Abu Dhabi Ocean Racing was already behind at this stage). As overall leaders in the race, Telefonica had the most to lose and clearly the team and their boat’s engineers back in Spain felt confident that if they sailed gently to Cape Horn the delamination would not propagate. With Camper and Abu Dhabi already both limping towards Puerto Montt, Telefonica also had the cushion of a big gap behind her. Conversely Camper, the first of the trio to experience structural problems took a more cautious preventative approach in heading to Chile.

Frostad also points to Team Sanya’s collision on leg one, when something in the water is believed to have punctured her hull in the bow. While not a great deal can be done to prevent collisions, of more concern was what happened to the layers of uni-directional carbon fibre once the collision occurred, the force of the water simply peeling them away. A simple fix for this in the future would be to require that the outer layer of the external skin be a woven biaxial fabric.

This race is of course not the first time that the VO70s have experienced severe damage. On the last race on the way up to Qingdao the fleet was decimated as they sailed upwind. Ericsson 3 suffered damage to the outer carbon fibre skin, as well as delamination of both inner and outer skins in a large section of the bow and had to be repaired in Taiwan. Delta Lloyd, the former ABN AMRO One, had a cracked bulkhead and delamination in her bow and ended up being shipped to Rio. Most serious of all was Telefonica Black which experienced a compression failure on her starboard side, resulting in a 2m crack running from the sheerline to the waterline. Green Dragon broke a forward bulkhead between her two watertight bulkheads forward which they were able to repair at sea, replacing the bulkhead once they arrived in Qingdao.

But with the rig and structural failures combined in this race, there is no denying that there has been more breakage this time around than we have seen before, despite this being the third race in VO70s. This has perhaps affected the race more since there are less boats in it and also because the stopovers are substantially shorter, although it is impressive how the teams have managed to effect repairs even in the tiny amount of time allocated to them. Frostad also feels that in past races there have been slightly bigger gaps between the boats and this perhaps allowed crews to slow down a bit more and second the issues they experienced perhaps were less severe allowing boats to make the finish of individual legs.

Frostad argues that VO70s are at the cutting edge of monohull technology and we wholeheartedly agree with this. Who would have thought it possible that a monohull would be capable of covering almost 600 miles in a day (Ericsson 4’s record from the last race stands at 596.6 miles)? To put this into context this is only slightly slower than the 2000 generation G-Class maxi multihulls that were some 50% longer – Steve Fossett set a new world 24 hour record of 580 miles on the then 105ft long PlayStation in 1998, while Grant Dalton took this up to 625 miles on the 110ft catamaran Club Med in 2000 (a record very nearly broken by Yvan Bourgnon and his crew on an ORMA 60 that year).

A contributing factour we suspect is that because VO70s are monohulls, they don’t get sailed with the same degree of respect as multihulls which are well proven as machines capable of destroying themselves if sailed beyond their limits.

“The boats are fast,” says Frostad. “I don’t think they are poorly built or engineered. The VOR is at the front of learning of the whole industry. Fatigue could be an issue, combined with the speed that they do and the righting moment. It is tricky.”

At present though there is the bigger concern for Frostad – that is to get more boats on the start line of the next race in 2014. While there was an attempt to cut costs this time around, this seems to have only worked to a limited degree and a more wholescale chopping of budgets likely to be put into effect for next time.

“We have no choice, but to address that,” says Frostad. “Some people are saying that now is the time to change the boat because of the problems, but our initial plan is to look to drive down the costs. Of course we would like to fix what we can fix to avoid the rig problem. If there is an opportunity to make the boats stronger we would like to do that as well.”

At present Frostad says they are investigating four or five options for the boat for 2014 the result of which they will announce in around a couple of months’ time. These options range from a 65ft one design to modifying the VO70 rule to reduce costs. “We are working a lot on it. We are going very far down the road with each of the options because we need to understand all the detailed consequences and the real numbers.”

If they do stick with the VO70, an important ingredient will be to try and find a way of making existing boats competitive so they can be sailed in future races.

Frostad says their target is to reduce campaign budgets so they are under 15 million Euros, compared to the 20-25 million they are for campaigns with new boats this time around. In the scheme of things Frostad adds that while costs haven't come down for this race, they did succeed in preventing them from rising at a time when costs of carbon fibre, etc are escalating. “To make a dramatic change you have to cut much deeper into what we are doing.”

At present the boats, including their sails and spare parts equate to 30-45% of a team’s budget, depending upon the amount of time they spend in R&D and design. So despite arguments that there are other aspects that should be addressed before the boat such as the number of stopovers being reduced, the boat is clearly a significant part of the equation. Frostad adds that they are also starting with the boat as this is a decision that needs to be made as early as possible as it is one of the first things teams entering the next race have to look at. However he acknowledges that the tight schedule for the race and the shorter stopovers means that the cost of shore teams has risen, although he adds “so the real boat cost, you could argue, is even bigger...”

After the boat Frostad says they will certainly have to reappraise the race too - its duration and number of stopovers and the format of the stopovers, as these clearly represent a significant costs for teams. “We have changed a lot of things for this race and we have learned what is working and the areas we might not have been so efficient. We could look at having some more pitstops in Europe to save time for example.”

As a ex-multihull sailor, Frostad says they have considered going multihull. They looked at the MOD70 and had some discussions with the organisers of that circuit. However the MOD70 one design trimaran specifically hasn’t been built to sail in the Southern Ocean and as a result their round the world race, the Ocean World Tour, due to start in October 2013, is going ‘the pretty way’, westabout through the Panama and Suez canals.

Frostad adds that a suitable multihull for the Volvo Ocean Race would have to be longer than 70ft and this certainly wouldn’t be any cheaper, although what if they went one design? The price tag of 3.5 million Euros for the later MOD70s (the ones they are making some money on) would surely be less than a VO70 at present?

But the fact is that getting Volvo sailors to compete around the world in multihulls is asking for trouble. If they don’t break them, they’ll capsize them. Even Franck Cammas wasn’t in favour of this when we spoke to him. Frostad points out that apart from The Race and the Oryx Quest, the majority of round the world voyages in large multihulls in recent years have been on record attempts not races. These lack the same competitive element you have when you have another boat alongside you. He also believes that monohulls work better than multihulls for television, they look faster, they heel, etc.

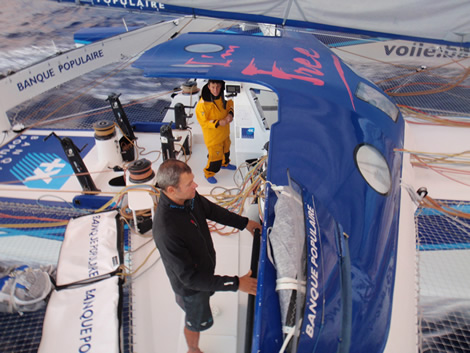

Another issue that must be addressed, which both Ian Walker and Mike Sanderson brought up in our recent interviews with them, concerns the safety of the crew due to the amount of water cascading back into the cockpit when the boats are travelling at speed. In the IMOCA 60 class many boats are now fitting retractible canopies over their cockpits (see this one), while maxi-multihulls such as Banque Populaire have a full-on windscreen at the front of their cockpit, windage be damned... Something similar needs to be made mandatory on whatever option Frostad and his team conjure up for the next race.

Latest Comments

James Boyd 25/04/2012 - 12:18

Thanks Tim. Unfortunately there is a danger that both the VOR and IMOCA 60 classes may go one design, which will mean there is no offshore development class apart from the Multi50 and the Minis... This cannot be good for the sport in the long run.Tim Penfold 25/04/2012 - 09:07

Excellent article James, it's great to get detailed factual information about the different breakages without the sensationalism. It will be very interesting to see what they do for the next race. Let's hope they can get more teams on the start line.Add a comment - Members log in