Ian Walker assesses the Abu Dhabi VO70 breakages

For British fans of the Volvo Ocean Race, the breakages on leg five of Abu Dhabi Ocean Racing’s Azzam were disappointing, but not in a comparable way to that felt by her crew, led by double Olympic silver medallist Ian Walker.

Having turning back to Auckland soon after the start of this last leg after the bulkhead supporting their J4 pulled out and then rejoining the race, so on 29 March, while in the depths of the Southern Ocean, an area of core failure was noticed in the hull of the Abu Dhabi boat, forcing them to slow down. Ultimately they followed Camper into Puerto Montt, Chile where due to the time constraints to get to Itajai for the start of leg six they had no choice other than to retire from leg five. These incidents followed their dismasting on the first night of leg one, when their boat ended up being shipped to Cape Town.

According to Ian Walker the core shear was the first structural failure they experienced in this race. “If you’d asked me in Auckland I’d have said we were in pretty good shape structural, but then we had the two failures on this leg...”

On their boat, the supporting structure for the J4 is a part bulkhead rather than a full bulkhead (which some other VO70s have) but in the heavy upwind conditions the boats experienced on the way out of Auckland it pulled cleanly out of the boat. When they returned to Auckland they tidied it up and refitted it, beefing up the bond between the bulkhead and the hull. Walker says they still don't know the reason why this breakage occurred and he reckons they never will.

“I’m sure if we had sailed the boat harder in J4 conditions before the race, we would have found it out. But you never know what might compromise something beforehand. Maybe slamming upwind broke the bulkhead away in an area which then led to it pulling out. Maybe we damaged it on a previous leg...”

Before talking about the core shear that occurred later, Walker first qualifies his thoughts. They have yet to take core samples and carry out forensic work (this will take place when the boat arrives in Itajai) so they can’t be certain of the reasons for the breakage – a point of view shared by Pat Shaughnessy, CEO of Farr Yacht Design who designed the boat.

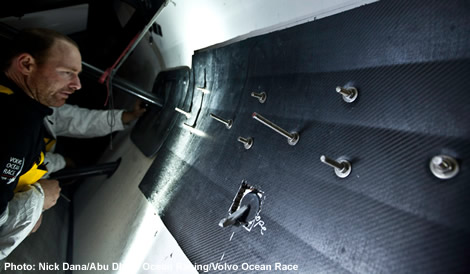

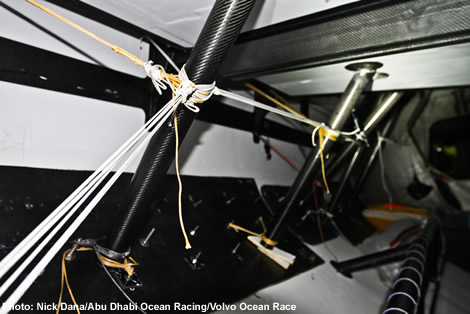

Significantly the core failure happened not in the bow area, but half way down the length of the boat at the chine on the port side, outboard of the bulks in the main cabin. “Basically the core failed where the core was bent around the corner - where the curve was too tight to use our normal Nomex, we used overexpanded Nomex which could be bent around the corner,” says Walker.

Mid-ships on the side of the boat is hardly a traditional slamming area and Walker points out that in the slamming areas, the Farr office was very conservative in the structuring of their boat using foam [as opposed to Nomex] in the hull forward of the mast. In fact the Abu Dhabi Ocean Race boat hull has a thicker than normal 40mm core, which should also make it more resilient to slamming.

“It failed in a fairly low stress area, not a traditional slamming area, and not an area where you’d normally have a problem, so maybe we fell off one big wave in pretty extreme conditions that popped it and that was that. Maybe you could sail the boat another 50,000 miles and it would never have happened. Or maybe we damaged it when the mast fell down, maybe the bunk attachment on the inner skin affected it. Or maybe it failed because of the curvature of the core. Until we analyse it, we won’t know.”

The impact from a collision is unlikely half way down the hull and as far as any damage that may have occurred following their dismasting on leg one Walker says they ultra-sounded it at the time and there wasn’t any damage to the external skin.

Pat Shaughnessy, CEO of Farr Yach Design shared his thoughts: “The core failure that occurred in the hull topsides is well aft of traditional slamming zones. At the time of the failure, the boat was reaching at relatively high average speeds. Detailed inspection of the area has not yet occurred, and the cause of the failure will not be understood until the area is removed for repair. We are pursuing a number of potential failure theories, however we need to consider that the type of honeycomb core used around this part of the curved section of the hull panel may have been subjected to loads beyond its capacity. Further explanation may be available after forensic work is completed in Brazil.”

Another significant problem for Walker’s team and the cause of their retirement from this leg was where the incident occurred – in the depths of the Pacific section of the Southern Ocean, 1500 miles from Chile and 1260 miles south of Easter Island. In reality, their situation was no different from that of Telefonica, which also experienced some core shear, only the Spanish boat was nearer to Cape Horn with a forecast that would allow her to get there to effect repairs in moderate conditions.

“If Groupama had broken their mast where we damaged our boat, they would still be somewhere near Cape Horn under jury rig,” says Walker. “If we damaged our boat where Groupama dismasted, we would probably have just sailed on to the finish. The problem was we couldn’t take on 1500 miles of Southern Ocean and Cape Horn with a very windy forecast with effectively only 1.5mm of carbon fibre on the outer skin in the main cabin of the boat. Also we were so far behind because of the weather after starting late, that by the time we got to Chile, there was no time to repair the boat and get to Brazil in time for the restart or repair it temporarily and get to Brazil in time to repair it properly for the restart.”

So as a result they were forced to ship the boat to Brazil, an operation which turned out to have its own problems. The ship it is being transported on was four days late arriving in Puerto Montt due to bad weather. It was subsequently delayed leaving by the Chilean coastguard, so its ETA into Brazil is now 17 April, giving them just three days to fix the boat and for it to be ready for the Pro-Am race in Itajai on 20 April.

Despite reports of hitting speeds of more than 40 knots on the previous day, Walker also doesn’t believe that at time of the breakage they were pushing the boat too hard. “When we broke our boat we think we were backed off. We consciously put in an extra reef in to back off. And we had nothing to race for - we were 1000 miles behind the next boat... If you look at speeds the teams were doing, I don’t think anyone sailed that fast. It was very rare that anyone averaged 20 knots and that is nothing in these boats. Ericsson 4 averaged 24 knots for 24 hours in the previous race. So it is not like everyone was going faster than they have ever gone before.”

However he points out that at times on VO70s it is not easy to back off. Upwind it is not a problem: you can reduce sail, drop the canting keel down, put sails blow, etc and as a result you will jump off waves less. “That is something we all learned on the way to China and we have all employed on this race.” Downwind you can back off by bearing away more and running flat with the sea state.

The problem are the points of sail in between. “Reaching is a lot harder especially at night when it is pitch black and you can’t see which waves have got backs to them and which haven’t. We were pretty throttled back - we only had about 30 knots of wind and we had two reefs and a J4, which is not much sail area. The hard bit to control is if, say, you are averaging 18 knots, one minute you are doing 13-14 and the next minute you are off down a wave doing 35-40 knots of boat speed. What are you going to do to go any slower? Take the mainsail down and just have the jib up? Then you go 8-9 knots and get swamped by waves breaking over the back of the boat. It is easy for people to sit at home and pontificate about how you can back off. Actually it is very hard and the only real way to back off is to run downwind.”

But even this isn’t without issues – with less sail up so the boat is more upright and it slams more and running downwind, going slowly or heading anywhere other than east in the Southern Ocean, particularly if you have a specific destination to get to such as Cape Horn, leaves a boat more susceptible to the giant weather systems that roll through this area.

“There are certain speeds you need to make at times in order to have better sea states and winds to be able to navigate as well as possible,” Walker explains. “The skill is obviously to know exactly when to back off and how.”

This is entirely down to gut feel, experience and instinct. Walker points out that the boat has load cells on the tacks of all the sails, but that doesn’t tell you when a panel in the hull is going to fail. “How do you know when you are going to go over a particular wave that is going to drop the boat in a certain manner that is actually going to make the side of your boat implode? If you sail around so scared of that the whole time, then you will come last or you won’t even make the next restart. We’d still be out there doing 10 knots.”

Yes, there are products on the market that allow you to bond fibre optics into the laminate of hulls (as they did on the multihulls in the 33rd America’s Cup for example) but even these won’t predict a rogue wave or the boat falling off a wave in an odd way during the middle of the night.

This is one of the significant problems researching cutting edge technology in ocean racing. Formula 1 teams have car that operate in a much more easily defined environment - the race track, albeit in a variety of conditions of dryness. If Volvo Ocean Race campaigns had similar operating budget they could for example send a race boat around the world the year before the race to test all of the new technology, it still might not uncover that one unique alignment of circumstances that would cause a failure.

Saying that, Walker agrees with Mike Sanderson in that more testing being allowed pre-race would certainly reduce failures although it wouldn't eliminate them. In the meantime the situation remains the same as always: with teams and the specialists they contract to make calls throughout not just the race, but particularly when their boats are being designed and built, of risk versus reward, based, in the case of sailors, on experience and in the case of designer and structural engineers on experience, science and computer modelling.

At the end of the day the Volvo Ocean Race remains the most competitive fully crewed event in offshore racing and it is a race. “The reason things break in the Volvo is that people still feel the need to chase the tiny incremental performance benefits, and the reason for that is that the standard is so high and everybody wants to win,” says Walker succinctly.

While race organisers will do the utmost to get class rules written so that they increase their boats' safety and reliability, on the other side of the coin in this competitive environment there will always be smart designers whose job it is to exploit those rules to the fullest degree.

“Because ultimately the Volvo Ocean Race is a boat speed race, you have to be fast because that has what has been proved in previous races," Walker continues. "Therefore designers and builders are under intense pressure to save weight everywhere you can, throughout the whole process, within the constraints of the rule. If you built everything so that nothing ever broke, you’d just come last. Even if the displacement was increased more, for instance, people still wouldn’t do it because they’d want to concentrate the weight in certain areas. It is all a product of trying to build a fast boat in what is a very professional race won by small margins.”

Farr Yacht Design’s Pat Shaughnessy agrees with this: “These are high tech platforms, being pushed to the absolute limits, in extremely unforgiving circumstances, and in an extremely competitive environment.

“I believe that it is possible to design and build a boat that won’t break, but I’m not sure our sailors would want to race in that particular boat because chances are it won’t be competitive in a mixed fleet. I believe that you can maintain a boat such that it never experiences failures, but I’m not sure our teams have the time or budgets available to achieve that. I believe that you can sail a boat such that it never experiences failures, but not in a competitive way. And I believe that you can have a race that never puts boats in harm’s way, but I don’t think it would be the Everest of sailing. I don’t believe that you can necessarily do all of those things together and expect it to be exciting, and competitive the same way this race has been in the past.”

However Shaughnessy acknowledges that this doesn’t mean they shouldn’t do better.

Going forwards, you can speculate about what might be done about the VO70 rule, but this seems academic as the race organisers are currently reviewing the type of boat they will use in the next race and the principle driving force behind this is not reliability but cost in order to get more boats on the start line in 2014 (as Knut Frostad will explain in an interview we’ll be publishing next week).

For Walker there is an additional concern he feels must be addressed (as did Mike Sanderson) and that concerns the safety of the crew and specifically the lack of protection on deck: “It is heinously dangerous. You just have to see the pictures coming off the boats now with water washing people off the deck. I got washed off the wheel. With the boat we are under a lot of pressure to build a boat that is fast upwind in light airs all through the Tropics and it has to now be able to do 10 in-ports, where you have to be able to drop the spinnaker down the back hatch, etc, and you also have to be able to have four guys on deck in 40 knots in the pitch black being fire hosed. You speak to Thomas Coville who has sailed Open 60s and trimarans – he can’t believe it. It can’t be right. That is a fundamental issue.

“What are we trying to do? Are we trying to sail around the world, in which case we should have an offshore boat that gives some protection for the crew, or are we trying to do a series of in port races and sail upwind through the tropics, in which case we can have boats with no cabins and flush decks, etc. The designers are under a lot of pressure, getting pulled in all sorts of different ways. We have had a lot of injuries. It is lucky we haven’t had anything worse.”

This is the exact same argue that was made a few years ago about the ORMA 60s - are they offshore or inshore boats?

Latest Comments

381394 13/04/2012 - 11:52

Fascinating article, no doubt prompting plenty of armchair reaction. Here's another I'm afraid. I've used over expanded Nomex in areas of high curvature in multihull hulls and have had failures, and now think it has no place in offshore hulls due to reduced sheer properties in the expanded plane. I'm not a great fan of nomex in any carbon offshore hull as we found to our cost in early multihull carbon structures. The structural package is just far too brittle and unforgiving. The V70 hulls could be made far more durable by banning honeycombe cores and instigating a minimum core sheer value without detriment to the yachts performance. Perhaps it would add 400kg to the hull weight, but so what? It would be the same for all. We can cope with rudders and rigs failing, but I thought the days of chopping up bunks was history. Its unfair to blame the crews as they have no idea where the design limit resides - nor do the designers as who knows what wave awaits them in the dark?Add a comment - Members log in