The nav effort

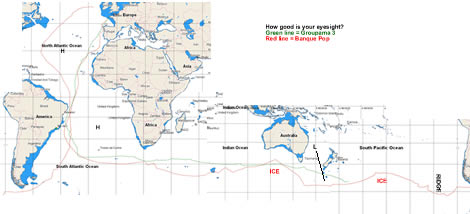

Unlike Groupama 3’s Jules Verne Trophy attempt in 2010, when the prospect of breaking Orange 2’s record was in the balance until they were back into the North Atlantic, on Banque Populaire’s lap, a fast initial passage down the Atlantic, causing them to lop 2 days 16 hours (or 18%) off Groupama’s time, set them up. Aside from a disaster occurring, such as the boat breaking or a collision, the possibility of their not breaking the record never really came into question, even through their lead over Groupama’s virtual progress plummeted from a high of 2364 miles when they were in the Indian Ocean, to just 528 miles after their painful Pacific crossing.

Certainly Banque Populaire is longer and more powerful than Groupama 3 - in addition to the team and her designers, a tribute must be paid to her original skipper Pascal Bidegorry for his key role in the boat's conception – but another vital part of the 40m trimaran’s successful Jules Verne Trophy attempt was her nav team.

This was handled on board by Spain’s Juan Vila and ashore by weather router Marcel van Triest, previously the maxi-tri’s navigator, who was on board, for example, for their west to east transatlantic record in 2010.

The Banque Populaire Jules Verne Trophy attempt was the first time Vila and van Triest have worked together, although they have raced against each other on countless occasions, both around the cans and around the world.

“We talked several times a day on email and sometimes on the phone as well,” says Vila, whose illustrious career has included four Volvo Ocean Races, winning on illbruck in 2001-2 and four America’s Cups, victorious in Alinghi’s afterguard in 2007, but three years later losing on the Swiss big cat, alongside Banque Populaire skipper Loick Peyron. “All the difficult strategic decisions we made them together. We exchanged opinions and analysed the data together and then we looked at the options, made a decision and went for it.” With Vila and van Triest, Peyron was also instrumental to the nav process.

“We talked several times a day on email and sometimes on the phone as well,” says Vila, whose illustrious career has included four Volvo Ocean Races, winning on illbruck in 2001-2 and four America’s Cups, victorious in Alinghi’s afterguard in 2007, but three years later losing on the Swiss big cat, alongside Banque Populaire skipper Loick Peyron. “All the difficult strategic decisions we made them together. We exchanged opinions and analysed the data together and then we looked at the options, made a decision and went for it.” With Vila and van Triest, Peyron was also instrumental to the nav process.

From his lair in Majorca, van Triest, harnessed some serious computing horsepower to enable him to process typically 1GB of weather information each day via three computers and five 24in monitors, running six Adrena programs simultaneously... In fact he probably suffered more than the crew over this 45 day record as although he wasn’t getting wet or working up a sweat sail handling or moving sails around, he wasn’t on a watch system and would get much less sleep each day than the crew.

His role was principally to look at the long term forecast and provide Juan Vila with second opinions. He was also instrumental in advising the team about their strategy for ice avoidance. This proved to be of paramount importance in their successful negotiation of a very tricky Pacific.

“It is a very probabilistic approach,” says the towering Dutchman. “A lot of my communication with Juan was screen shots with notes on them and a cluster of routing and identifying the forks in the road. ‘We have to decide four days from now and it depends on if this or that is going to happen.’ And also we were trying to postpone the forks in the road basically – if you can keep that four days ahead of you, all the time, then you never need to take a decision.”

Occasionally, such as the awkward crossing of the Doldrums outbound, he would get involved in the short term forecasting. “Or when I was keen for them to gybe! But watch-by-watch running - like ‘it is going to build’ or ‘you have to shake a reef’ – I let Juan deal with that,” says van Triest. “I would ask Juan questions like how the sea state is evolving and that sort of stuff. And I would send them the occasional email when I thought they were slow!”

Suggest you click on this image to enlarge it

No surprises

Van Triest works with weather models that provide forecasts looking 15 days ahead, so the decision to leave was a tough one given that it had to be favourable for the entire southbound Atlantic passage. From starting it took the 40m long maxi-tri just 11 days 21 hours 48 minutes to pass the Cape of Good Hope. So with the forecast from the start van Triest says they were already looking at how they might enter the Indian Ocean.

“When we left we said ‘the Equator is going to be okay - not earth shattering. The South Atlantic - we are going to have to sail more miles than Orange 2, which sailed straight, but there is wind around the systems, so it is doable. We will be doing 750 miles a day, it is just extra distance. That is why we decided to take it.”

While they were at sea, van Triest would run the routing every six hours for up to 10 days ahead, second guessing how the met scenarios would unfold.

A 40m long maxi-trimaran with a top speed well above 40 knots and capable of covering 908.2 miles in a day (a record Banque Populaire set during her west to east transatlantic record in 2010) provides the navigator with considerable flexibility. Almost all of the time, it allows them to play the conditions, rather than conditions to play them. Given Banque Populaire’s polars, the nav team were obviously looking to stay in optimum conditions and thus avoid light or extreme winds. Vila says this was typically a range between 15 and 30 knots of wind speed. However it was the sea state that they were particularly concerned with and Vila says here the aim was to avoid areas where there were waves larger than 4m.

Because of the nav team’s continual consideration of the weather looking ahead combined with Banque Populaire’s speed potential there was just one occasion on the whole lap of the planet when they were forced to sail in unfavourable conditions – a lumpy patch to the south of Tasmania.

Heading off

According to Vila the crossing of the Doldrums outbound was not straightforward. “The Doldrums were very wide and we didn’t want to spend a lot of time becalmed there, so in the end we found a cloud pattern that might help us and it was coming from the east, which was why we went probably a little further east than we would usually go. That was a key point.”

The run down the Atlantic outbound essentially went according to plan and, despite a big detour west around the St Helena high, Banque Populaire still managed to pass the Cape of Good Hope setting a phenomenal new record.

Their course through the Southern Ocean was unusual in that they had to duck and dive to avoid ice and the more furious depressions. In the Indian Ocean they passed south of the Kerguelen Islands, which is not something we have seen recently. Van Triest points out that had the ice situation in the Indian Ocean been the same as it was a year ago for the Barcelona World Race (which he supplied the weather data for), then Banque Populaire’s Jules Verne Trophy record may well have ended there.

They then had to head north towards Australia to avoid a severe depression, but this worked well as it also enabled them to steer north of a zone of ice.

As mentioned, the only tricky weather decision of their voyage came as they were considering how to pass south of New Zealand with a depression developing in the Tasman Sea (between Australia and New Zealand) and then heading their way. Vila says the choice was between shaving New Zealand’s south island or heading deep into the Southern Ocean. In the event they chose the latter option.

Ice

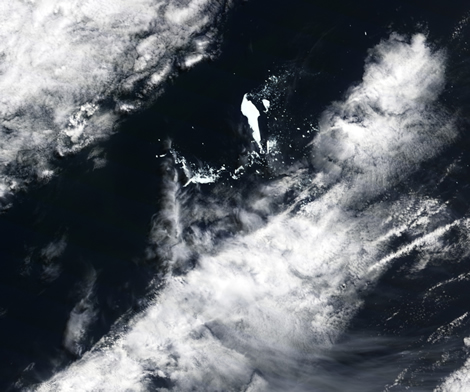

Certainly the hardest and most stressful part of the voyage for the crew, and for van Triest, came in the Pacific thanks to the giant iceberg B15-J having recently calved.

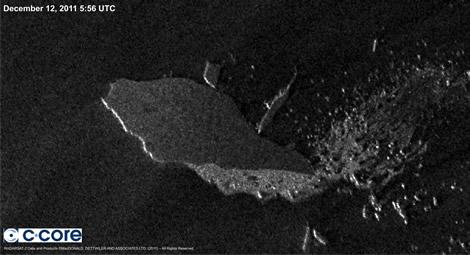

To help ease them through this area van Triest worked with several specialist companies, including satellite image analysts at C-Core in Newfoundland, but it was also essential to get hold of up-to-date satellite images showing the location of the icebergs in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

According to van Triest it is possible to get these satellite images from organisations like the European Space Agency, however this has to be planned well in advance. So they also order images from another Canadian company that itself owns satellites. “With a commercial operator you can say ‘I want that image tomorrow’ and you can get it, but it is not cheap!”

The area of the satellite image and the resolution also determine the cost of the satellite images. Usually van Triest worked in ‘wide swathe mode’ ie images covering a 500sqkm area with a resolution down to 100m. However in particular areas of concern he would also use higher resolution versions covering 10sqkm with resolution down to 1m.

Thanks to this, the nav team could steer Banque Populaire through or away from ice with greater finesse than would be the case with round the world races. As van Triest states: “With round the world races you say ‘there is ice there’ and you put in an ice gate well north of it, but you never knew if the information you had was true. Now we do.”

However even then it was not a case of downloading a satellite image and then the crew identifying individual bergs as they flew past. “It is amazing how quickly they move around,” says van Triest. “We had a lot of current files and that is expected, but there is always half a knot of current and sometimes up to a knot, which is 12-24 miles a day. So how we dealt with it was that we actually aimed for the target which was the biggest guarantee of not seeing it!”

As a result Banque Populaire’s passage through the Pacific became something of an iceberg tour, the most impressive being the crew getting to see the giant berg B-15J (read more about this here). Generally they avoided ice, as was the case in the eastern half of the Indian Ocean, however in the mid-Pacific they chose to pass through an area where a few bergs were showing up on the maximum resolution images.

“We decided this for several reasons - to keep on aiming at the record, but also because we were on the wind which gives you massive liberty in route changes – you can bear off and tack, etc,” explains van Triest. “If you are downwind hauling ass, you can’t luff because you flip over and you can’t gybe without furling and you need all the guys on deck and all of a sudden you have already done 10 miles and you are into the wall.

“We were also in warm water –8°C. So the thinking was that if it was 7-8°C, a growler can’t live on its own for a very long time. So as we know where the big ones are, we should be okay and if there is a growler it should be fairly close to the big one and we can give it a wide berth and we should be fine. Then slowly on our way out of the iceberg area, we started to get into colder and colder water and then we came across one isolated growler without any ice. Then you think ‘^%$^%$!!!’.”

In addition, thanks to being in the southern hemisphere summer at high latitudes, there was only around one hour of darkness each day.

A secondary effect of going so far north to get through the ice zone in the Pacific is that it left Banque Populaire with a ridge blocking the way between her and Cape Horn. Annoyingly this ridge was moving east at much the same speed as they were and as a result it proved impossible to penetrate. Ironically this came at the same time as the Volvo boats were facing the same problem with a trough/weak front as they headed east from Cape Town.

“If we had got through that ridge we would have saved two and a half/three days,” Vila reckons.

Homeward bound

The passage up the south Atlantic was quick, but once into the North Atlantic, the Azores high was particularly enormous and as a result Banque Populaire was forced to carry out a huge detour west – they crossed the Doldrums at 33°W but ended up sailing to 53°W (within 600 miles of Bermuda) – to avoid being caught in light winds.

“It was the safe option to take, because it was quite scary to go straight and get trapped in the high,” says Vila. “Actually as we saw it develop later we were happy with our decision to sail more miles, but at least ensuring that we would be at the finish with a good advantage still.”

Developments

Historically the European and NOAA GFS global weather models have proved good forecast for the northern hemisphere but have been less accurate in the Southern Ocean.

As van Triest recalls: “I remember in the late 1990s [when he was navigating Intrum Justitia for Lawrie Smith] South Pacific models - you didn’t even look at them. I’d draw my own weather maps. It was completely out to lunch.”

However since then the situation has dramatically changed, which van Triest says is down to the increased input of satellite information being fed into the models.

Other there is still much work to be done in terms of tracking and locating icebergs in the Southern Ocean and also into wave conditions. Of the latter van Triest says: “Maybe we have to do some calculations ourselves because wave height and direction are irrelevant - it is all about wave ‘solerity’, the length of the wave relative to the height, and the propagation of the waves.”

Latest Comments

Add a comment - Members log in