IRC-HPR hybrid 40 footer

Since we lasted looked at the handicap 40 footers market (Farr 400, Ker 40 and McConaghy 38), several new offering have come available including the high performance Carkeek 40 built by Premier Composites in Dubai (now in its Mk2 form) and McConaghy-built Botin 40.

But the first of this latest generation of boats of this size to arrive in the UK, in the form Richard Matthew’s Oystercatcher XXX, is the Judel-Vrolijk designed 42ft built by Hakes Marine, the HH42.

When we last wrote about Hakes in any major way they were based in Wellington, NZ, when they were building TP52s and subsequently Mike Golding and Dee Caffari’s IMOCA 60 sisterships. Since then they were forced to shut up shop in New Zealand before re-emerging as part of Hudson Yacht and Marine, a giant conglomerate based in Xiamen, China.

Most significant about the new HH42 is that it has no pretentions of being a one design, to the extent that it has been created to be competitive under any of the current trio of rating rules now being sailed under – IRC, obviously, but also the increasingly popular ORCi and HPR. Each of these prefers a particular type of boat – for example HPR is, like IRM was in the day, aimed at high performance yachts. Sadly in IRC’s case the type of boat that finds a favourable rating has been found to vary according length: lighter, higher performance boats seem to work better when they are longer, while the rule seems to prefer heavier, more conventional, production cruiser-racers at at smaller sizes. 40 footer are erring into the latter territory.

As Antoine Cardin, naval architect with Judel-Vrolijk, observes: “The main issue with 40 footers under IRC is that we have to end up with a more conservative design compared to a TP52 for example. A TP52 will definitely perform well under IRC and is quite an extreme racing boat, but if you scaled one directly down to 40ft, IRC seems to be more severe on [performance boats] at this size. So for a 40 footer you need to be more conservative under IRC.”

So to optimise a 40 footer for IRC the boat needs, in particular, to be heavier. Cardin continues: “You try to add some weight in places where the rating under IRC might not see it properly and you would definitely do a more conservative design with maybe less sail area to displacement ratio, so you lose on performance, but gain with the rating.”

Conversely HPR favours lightweight performance boats.

So how to come up with one boat that will work with both rules? Key is the pre-preg carbon fibre construction of the HH42’s hull, deck and structure and this allows different keel configurations and constructions (and weights) to be used to tailor the boat’s displacement and draft to which ever rule the boat is to be raced under. “That is quite straightforward to achieve for the Hakes 42 approach,” says Cardin. For with the HH42 this is no mere tinkering – in IRC configuration with a lead bulb and cast iron foil, the boat weighs 5 tonnes, whereas for HPR the bulb can be smaller and foil made from fabricated milled steel or even carbon fibre, for those really intent on going down this path, ended up with a displacement as low as 4.25 tonnes.

Of course the magnitude of this kind of displacement variation has implications for the hull shape and how it sits in the water, but the Vrolijk office took this into account when they designed the boat. “We looked at the displacement and different trim of the boat, to make sure that the boat is flexible for different set-ups. So we can play with +/- 500kg displacement easily while keeping acceptable hull lines and the overhangs are designed for it,” says Cardin.

Obviously this also serves to help ‘future proof’ the boat, so that if at some point in the years ahead HPR, or an IRM type rule, truly gains a foothold internationally, then IRC-type HH42s can be fitted with a new keel and remoded in a ‘light’ configuration in order to be competitive against other high performance boats.

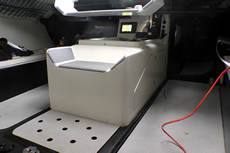

In addition to changing the keel and reducing displacement, an HPR optimisation would also see the vestigial interior in the boat, such as the head compartment, the galley and berths - there to alleviate their rating under IRC- removed, although as they are, they weigh barely anything. Significantly Cardin says that they would keep the same rig.

Creating female tools for production building the hulls in carbon fibre was also possible because of Paul Hakes’ background as a constructor of grand prix race boats. “Of course for IRC building in carbon is a cost, but it is logical: your boat is lighter, you have less inertia/weight when sailing in the waves, so your boat will perform better. But for us it gives us much more flexibility to tailor the boat to each customer,” says Cardin.

To date three HH42s have been completed – Richard Matthews Oystercatcher XXX in the UK, Paul Winkelmann’s latest Island Fling and a third due for imminent arrival in Australia. All of these are destined to race under IRC, while a fourth will be heading to the Baltic, where it will race under ORCi (the ORCi Worlds are to be held in Kiel in 2014) and the Vrolijk boffins are working on the best configuration for this rule.

So what sort of boat would ORCi produce? “That is more friendly to performance yachts. If you look to the previous Worlds last year, TP52s won,” observes Cardin. In fact of the top six boats at the ORCi Worlds this year, four were TP52s and a fifth was a canting keel Cookson 50.“So we will definitely keep a boat fast, but with ORCi we are mainly focussing on small tricks, that are directly linked to that rule, such as the draft and displacement which they don’t rate the same way as IRC.”

To our eye, the hull shape of the Hakes 42 looks similar to the Vrolijk TP52s, carrying the overall beam from midships back to the transom and with a significant chine, but according to Cardin this is not the case. “This comes from a new family of hull shapes we have developed. It is nothing like the TP52 Ran or All4One, which were from the previous family.”

Obviously the HH42 is not designed with the constraints of a box rule and as a result she has a proportionally larger Bmax for her length, with flare in her topsides and the wide beam at deck level carried all the way to the transom. This, along with small sidedecks that stretch all the way, enable the leverage of the crew hiking to be put to maximum effect and also for the crew to move aft as far as possible when sailing downwind.

Volume distribution is also different with Judel Vrolijk’s ‘new family’ of hull shapes and, thanks to the variation in displacement the boats is likely to see, the position of the chine is also different from their previous TP52s. “Here we tried to gain as much hull power and stability from the hull, while reducing heel drag as much as we can,” says Cardin, adding that there is added volume in the bow above the waterline in order to maintain the correct trim fore and aft as the boat heels. “We have also tried to reduce stern drag at high heel angles, which leads to these high chines – much higher than on the TP52s.”

Performance-wise, the aim was for an all-round boat, but inevitably with this style of boat, it is a weapon off the breeze with the compromise being upwind pace. This style of boats also seems to do well in light conditions (because they are light and easily driven) and heavy conditions (when they can plane earlier – around 14 knots in the case of HH42) but suffer in the medium, as is the case with, for example, the Ker 40s.

“We tried to keep the upwind in the mid-range of what is acceptable upwind, because if a fast boat lines up under IRC with a cruiser racer, it is hard to beat them upwind in 12 knots,” says Cordin. “That is another reason why we have a more conservative appendage package – so that the boat can be a potential winner in all wind conditions.”

However to give some indication of the performance available off the breeze – in the recent Hong Kong to Vietnam Race, her first offshore race and in which she won IRC 1, Island Fling hit 27 knots.

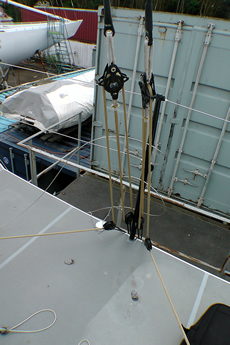

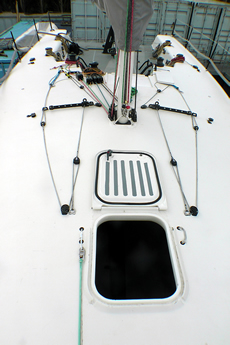

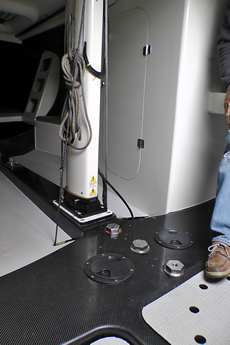

While the hull shape may have evolved since Judel-Vrolijk’s last TP52s, the deck and cockpit layout looks very similar to that of modern TP52s. Most obvious is the positioning of the single pedestal immediately aft of the mainsheet track that drives the primary winches. The pedestal is vital for the considerable speed boost it provides in manoeuvres, particularly hoists and gybes and it is positioned aft (a trend Emirates Team New Zealand set in the TP52s), along with the control for the vang (which emerges out of the cockpit floor aft of the helmsman) so that they can be operated by the crew from aft in the boat when sailing downwind.

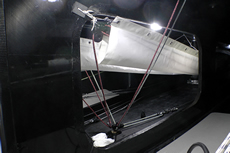

While it is not fitted on Oystercatcher XXX, Island Fling is even fitted with a pedestal-powered string drop line system down below so that kites can be sucked down the forehatch at a rate of knots, useful for those America’s Cup calibre leeward mark roundings.

The pit also borrows from development work carried out in the 52s, with a relatively small winch, as conventional pit operations, like grinding up halyards in hoists, is now carried out on the primaries, powered by the pedestal. Also like TP52s the helmsman’s position is well forward to enable easy communication with the trimmers.

However generally with the cockpit and deck layout there has been a move to simplify the HH42 in comparison to a TP52. For example they have not piped so much rope work down below. Downstairs on a TP52s it is like a cat’s cradle of lineage and purchase systems, whereas on the 42 more is left above deck, such as the jib fairlead up-down and in-out control lines. More control lines are also above deck simply because HH42s are expected to go offshore and minimising the number of holes in the deck helps prevent the boat turning into a colander (as some of the Med TP52s are). “That is also why the forward hatch is hinged as standard, rather than havinga a sliding hatch - to keep it watertight,” says Cardin.

This simplification also extends to the rig – Oystercatcher XXX has a Hall Spars carbon fibre mast, whereas Southern spars are standard. For example there are no titanium fittings and there is a halyard lock only on the mainsail, but not for the halyards on the front of the mast. According to Cardin, this is to keep costs down, although he feels having halyard locks throughout would be better for racing under IRC and of course they have been fitted on boat #2.

Similarly the standing rigging is stainless steel rod rather than composite. However to reduce weight aloft they have gone with a deflector system that allows the running backstays to be pulled into the mast at a lower position when using fractional headsails. Also the HH 42’s rig set-up lacks the rake adjustment that would be found on a TP52.

At present the first two HH42s have sails from North UK, while the third boat heading for Australia will be fitted with Quantum. While Cardin says that they would keep the rig the same when optimising the boat from IRC to HPR, what they might change would be the length of the bowsprit, so a longer one could be fitted, and in turn larger kites used, when sailing under the High Performance Rule.

Engineering for the HH42 was carried out by long term Judel Vrolijk collaborators Steve Koopman of SDK Structures, his job slightly complicated by having to consider the production build element of the boat. The interior of the boat is very ‘open’ structurally to make it easier for crew to move around the boat and drag sails around. It features just four ring frames, a moulded keel floor and two substantial stringers spanning the length of the boat.

In pretty much every aspect other than price (when she is much closer to the Ker 40) the HH42 falls in the ground between the Ker 40 and Carkeek 40. This is reflected in her IRC TCC – while Ker 40s are around 1.192-4, the HH42 stands at 1.224 (in IRC configuration). The new Botin 40 is slightly nearer the top of the range performance-wise with a TCC of 1.258, while the Carkeek 40 can be similarly optimised for IRC, when it has a TCC of 1.235 – as opposed to 1.270 (ie the same as the Ker 46 Tonnerre) in her HPR configuration!

Price of the base boat is US$ 497,700 including rig, but ex-shipping, tax, sails and electronics.

Vital statistics:

LOA: 12.6m

BOA: 4.35m

Draft: 2.8m

Displacement: 4950kg (IRC config)

Sail area (upwind): 106sqm

Sail area (downwind): 245sqm

Mast height (above waterline): 20.02m

E: 5.88m

J: 5.05m

IG: 16.31m

ISP: 18.71m

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Latest Comments

bdu98252 15/11/2013 - 16:49

What is with the rust stains on chainplates and keel interfaces. Is the quality control on stainless parts poor and fitting detail on the keel lacking.Add a comment - Members log in