Making the call

The photos in this article are courtesy of Gilles Martin-Raget/www.americascup.com

No stone has been left unturned in attempting to turn racing for the 34th America’s Cup into an event with maximum appeal to television and the non-sailing public. Lost slightly behind the more glamorous features of the new era America’s Cup, such as the wingsail catamarans has been how the Racing Rules of Sailing and the umpiring system have also had a complete overhaul.

The new 'Racing Rules of Sailing - America’s Cup edition' have been endorsed by ISAF, after they were created by the America's Cup defender, Oracle Racing, headed by their rules adviser Richard Slater, and members of Vincenzo Onorato’s Mascalzone Latino, when it was Challenger of Record. But central to the process, the middle man representing America’s Cup Race Management in the process, was Mike Martin, whose job was to ensure that the new rules met ACRM's goals of fast, exciting sailing, simple for spectators to comprehend, etc.

“With the different boats and trying to make it spectator-friendly, we have tried to simplify the rules and take out the ones which are confusing for spectators and sailors and umpires altogether,” says Martin, now Chief Umpire and who is also a former 505 World Champion. “A good example is the tacking rule, rule 13 in the old rules. We don’t have that rule any more. It used to be that you were tacking from the time you crossed head to wind until the time you were on a closehauled course. For us, you are either on starboard tack or you’re on port tack, just depending on your windward side, so the actual tacking is instantaneous. It makes it a lot cleaner and it takes out a lot of subjective calls.”

Another one, which regularly comes into play in match racing is rule 17, limitations on luffing. “Before if you gained an overlap from behind within two boat lengths, you didn’t have any luffing rights,” explains Martin. “We got rid of that one - so it is windward-leeward. We have the windward-leeward rule and it is in effect or it is not.

“Also with room at the mark – rule 18 – in the past there was one set of rules at the windward mark and a different set of rules at the leeward mark and we just eliminated that and it is the same at both. Right now the inside boat when they reach the zone, any outside boat owes them room. For example, if you are approaching a mark to round it to port, and you are on port tack, you have room at that mark. In the past you couldn’t come in on port tack at the weather mark, but under the new rules you can – you don’t have right of way over the starboard tacker, but the starboard tacker has to give you room to round the mark - which is the same situation as it’s been at the leeward mark for years. So we are just trying to make it symmetric up and down the course and trying to keep it simple.”

Some rules have been adapted due to the type of yachts being used. While reaching starts are used for the fleet racing, for the match racing the start line is skewed so that the port tacker now has the opportunity to cross ahead of the previously favoured starboard tacker or right hand entry boat.

The idea behind this is to try and prevent dial-ups, previously one of the most skilful parts of the pre-start. This is perhaps a shame, but Mike Martin explains: “Catamarans are all about speed and going fast and a dial-up situation in a catamaran is a bit scary when you have 40 knot closing speeds. So it has got rid of the dial-ups, but it has developed a whole new starting tactic and you watch the starts and they are really exciting because now they come out and they gybe and they start playing this game of chicken, trying to get below each other and hook the other boat. So there is lots of acceleration and hull flying and tight manoeuvring. It is a different sort of action. It is a bit safer than dial-ups and dial-downs, but it is pretty exciting nonetheless.”

The new rules also attempt to prevent dial-downs. “If you are going upwind, you can’t bear off to a downwind course which is more than 90 degrees to the wind in order to prevent a port tacker from keeping clear. You can bear off but you can only bear off to 90 degrees giving him an escape route,” explains Martin.

So penalties will most likely be for different things under the new rules? “Most of the protests under the old rules were for rule 13 – while they’re tacking - or rule 17 - right to luff. So we have eliminated most of those, but I think what we’ll see in ours is more rule 15 and 16 where if someone creates an overlap to leeward - did they give them enough room and did the weather boat do everything they could to keep clear? I think those are the protests we’ll see most often in the match racing.”

Martin says they have also rejigged some definitions such as Rule 18 – room at a mark – while he says Rule 20, the old room to tack rule, is significantly different. “In the past when you came into an obstruction and you wanted to tack you had to say ‘room to tack’ and the other guy either had to tack or say ‘you tack’ and then you had tack immediately and it was all a bit tedious and a bit ridiculous. And in 72ft cats there isn’t really time to say ‘room to tack’ and the other guys are not going to hear you anyway...”

With the new course boundary limits, where a team will be penalised if they run off the course, rule 20 comes into play a lot, so under the new rules when a boat gets to within three boatlengths of an obstruction then they automatically are allowed room to tack or gybe. Martin explains: “These boats aren’t designed to sail dead downwind like keelboats are and we want them to sail angles and sail fast, so any time you get in within that three boatlength zone you have room to gybe and sail your proper course, so it is good. You get to the wall and both boats have to either tack or gybe. So it keeps it exciting and there is a lot less trying to communicate back and forth. It is a very clean simple rule and I think it is good.”

As was demonstrated in Cascais when Winston Macfarlane fell off Emirates Team New Zealand, the boat isn’t allowed to go and pick them up – they must be recovered by the team’s RIB, and there is no penalty for this (despite what was said at the time). The penalty of losing a crewman on the already labour-intensive AC45s is considered enough of a penalty.

A rule which may well rear its head in gusty Plymouth next week will be what happened during a race should a boat capsize. In this event a team is allowed to receive assistance to right their boat, including putting any crew in the water back on board, and can then continue sailing. The emphasis is on getting boats to finish races and this is why there is the slightly unusual scoring system whereby the winning boat receives 10 points, and the boat that finishes last still receives three points. “We want an incentive for people to start and finish. If you go out and race you get three points and if you don’t, you get nothing. And also if you capsize there is an incentive for you to get up and keep going so that you finish the race. We just don’t want people sailing in.”

Of course whether this capsize rule will work with the AC72s is another matter. “We’ll see with the 72s,” admits Martin. “The first couple of times the 45s capsized it was 200 hours of work. But each time they looked at what broke and what went wrong and did some improvements and when Korea capsized they righted the thing and kept sailing. So I think that will get more and more common as we go along.”

Another change is that races can be 'terminated' (rather than 'abandoned') if conditions get too lively or too light. Usually when there is an abandonment the race is completely annulled, however under the new regime, when a race is terminated any finishers get scored while those that didn't are scored as DNF. This is designed to reward those who made it around the course, although one imagines it will make the Race Director, or whoever makes the call, fairly unpopular with the teams which didn’t finish.

Penalties

As we have touched upon in our video tours of James Spithill’s AC45, the way penalties are doled out is revolutionary and now highly dependent upon technology. On the main crossbeam of each AC45 is a special display with a light system indicating when a team has been protested, the yellow light switching off when a team has carried out its penalty. This display also has a red light that starts blinking when a boat is approaching a course boundary – like the reversing bleep in a car, this light blinks more rapidly the closer a boat gets to the boundary and goes solid red when the boundary is crossed, which in turn means a penalty is on its way.

To achieve all this is possible due to the pinpoint accuracy of the tracking and course boundary, thanks to the military grade GPS used throughout the event that is accurate to an incredible 2cm.

This has allows the penalties themselves to be changed. Due to the handling characteristics of the catamarans there are no penalty turns, instead a boat has to slow down and let the others catch up.

“What we did was make a VMG line and as soon as you are penalised this VMG line appears two boat lengths behind your current position and then it moves forward at 75% of your estimated VMG based on the polars of the yachts and you just have to dip behind that line,” explains Martin. “So as soon as you get the penalty it is really to your benefit to do the penalty as quickly as possible, and you are required to do it immediately. That is different from match racing in the past when you could wait until the end and you always see them swirling around at the finish, which causes some confusion.”

As ever the new regime aims to have protests dealt with on the water during racing and not after racing in a protest hearing. “You can’t file for redress for the action of the Race Committee, but the Regatta Director can. So if it was a real screw up, then Ian [Murray] can file for protest on the behalf of any yachts he wants to to make a fair decision. So what we are trying to do is when everyone crosses the line, that is the finish and there is no drama,” says Martin.

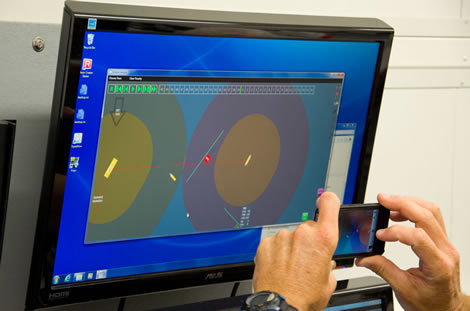

Much of the electronic side of this has been a secondary benefit of the work Stan Honey’s team has been carrying out, enabling marks, course boundary lines, boat positions, tracks, etc to be overlaid on to aerial video pictures shot from a helicopter. This has helped usher in a new era in umpiring, where on the water there is the normal RIB with two umpires on it, but also two umpires on jetskis and another two umpires in a booth ashore, watching the tracking and the video feeds from the race course.

“The technology and the data were there, so we were thinking this could be used for something good,” says Martin. “Anyone who has been in a protest wishes ‘if only we had a camera directly overhead with the zone signified and it showed that I had room, etc’. But the reality is that we have that now and it is interesting because the umpire can look it, make the call, can freeze frame and play it back and make the right call. The other day the water umpires called it one way and then reviewed the data with the booth and the booth said ‘no actually at the zone there was no overlap and this boat didn’t owe the other boat room’ and we were able to make the right call which would have been the wrong call without the assistance of the software.”

So between the umpires on the water and those in the booth – who makes the call? “To be honest we have been batting it back and forth to determine what works best,” says Martin. “What it really comes down to is the type of penalty. If it is a penalty of ‘did he have an overlap or not’ or 'what was the status of the zone?’ - that sort of decision is made from the booth, because they have got that perfect data. If it is a question of an overlap was created and did the keep clear boat do everything they could to keep clear - then that decision is made on the water.

“Also in the booth we have the helicopter feed and the program feed, so we have that information on hand, so that all goes into making the decision, and there is a short discussion - we are working on a procedure with keywords to convey the important points of who had rights and who didn’t, so that we can make the call quickly and accurately. We have been through both situations where all calls are made from the booth and all calls are made from the water, but really you need a combination.”

Jetskis are used because they are easier to keep up with the slippery catamarans, however finding umpires able to do their job while driving them has been an issue, says Martin. In Cascais one of the two was David Blackman, previously a Navy Seal. “Physically it is very demanding,” says Martin. “In San Francisco it is brutal. When we were doing the testing, there were a lot of very good umpires who came back with the response that I can make calls and I can drive the jetski, but I can’t do both at the same time. And a couple of navy seals were like ‘yeah, no problem’.”

Testing of all these new systems has been a work in progress since they first tested it earlier in the year with the AC45s in Auckland. They continued this in San Francisco when the Oracle boats were training there and subsequently in Cascais before the first America’s Cup World Series event.

And it remains a work in progress says Martin. “We have come a long way from where we were in New Zealand and the system is much more stable and we’ve have a lot of refinements and add-on and sometimes we’ve taken them back off. It is a learning progress and it is constantly being updates.” For example at one point the penalty system was going to be entirely electronic, says Martin, but it became apparent when they tried this, that the umpires and the crews knew what was going on, but no one else. As a result they reintroduced the usual system of flags, for spectators and the television.

At present OCS calls are made the traditional way but one imagines that with 2cm accuracy of the tracking this could be automated with ease too. Martin says this is under consideration in the future.

Obviously all this new technology is relevant to the particular style of racing used in the new era America’s Cup with fast catamarans and course boundaries and much of this will be irrelevant for the rest of the sport. The question is will any of it filter down?

“Several people have asked me if they are going to make it into the regular rules and it is a bit premature to say,” says Martin. “But even in the little amount of exposure we’ve to them so far, getting rid of the tacking rule (rule 13) and the limitations of altering course (rule 17) it simplifies the whole game so much. These are pretty radical changes. I think some of them will be adopted and some won’t. For example the whole penalty line concept relies on this accurate high tech GPS that most races don’t have access to.”

Latest Comments

Add a comment - Members log in