North Sails 3Di (part one)

For the last couple of years North Sails have been working on a development that looks set to be every bit as great a step forward in sail technology as 3DL was when it was introduced in the early 1990s.

Compared to 3DL, 3Di sails are stiffer, making for an aerodynamic improvement over 3DL and as the product is developed could ultimately end up representing a weight saving of 10-15%.

Development 3Di headsails are already being used on some race boats in the TP52 fleet, on Mini Maxis such as Ran and Alegre, the regularly raced Wallys Magic Carpet and J-One and Peter Harrison’s Farr 115 ketch, Sojana.

Origins

Unusually, like 3DL, 3Di was spawned in the small but creative sail making enclave in Geneva, Switzerland. There Gerard Gautier developed the product with long time partner Edouard Kessi. The duo that started 3DL, Luc Du Bois (subsequently with Alinghi) and Jean-Pierre Baudet, started their sailmaking careers with Gautier Sails. Baudet and Dubois then went on to sell their idea to North, while Kessi and Gautier sold their sailmaking business before moving on to concentrate on another business making handgliders and paragliders.

Gautier and Kessi came up with the idea of 3Di, and received some early development help from the ETH technology college in Zurich. They got money to develop the product from Alinghi’s Ernesto Bertarelli who ended up effectively owning the product – the mysterious ‘black sails’ trialled on the Swiss defender’s Version 5 boats prior to the America’s Cup in 2007, but in fact never used during the event itself.

Above: Artemis TP52

Following the 32nd America’s Cup the technology was sold to North Sails who since then have been developing not only the product, but also the complex machinery necessary to build it. Gautier and Kessi continue to work on 3Di but spearhead their research through the newly formed division of North Sails, North Sails R&D in Geneva.

The equipment to build 3Di sails was set up at the 3DL facility in Minden, Nevada in January 2008.

The technology

While their names are distractingly similar, 3Di in fact is a complete departure from 3DL. As we are all familiar, 3DL comprises a lattice of fibres laminated between two Mylar films, glued together under heat and pressure on 3DL’s famous three dimensional moulds. In comparison 3Di has no films and its construction process in fact is more akin to boat building, albeit in a featherweight way.

The 3Di construction process breaks down into three phases:

i) Making pre-preg tapes.

Key to 3Di technology is that it is based on pre-preg ‘tapes’ made by North as the first stage of the process. What we typically think of as a yarn, is in fact a bundle of filaments, each half the diameter of a human hair. Typically “yarns” come in bundles of 3000, 6000 or 12000 filaments. The North pre-preg machine, known as ‘the Pregger’, spreads out the filaments in a straight line and lines them up side by side before they are run through a resin bath. This tape is then mounted on to a disposable paper backer, removed in the next stage.

As normal with pre-preg, the tapes are stored cold until they are ready for use.

The pre-preg tapes are manufactured at 600mm wide, although they are cut down to typically 120mm for sail making (although any width is possible if the right head is put on the machine). But the main feature of the tapes is that they are uniquely thin.

Bill Pearson Technical Director North Sails 3Di and 3DL explains: “Because we had to make really thin, fine materials to be able to get sails light enough, we developed our own spreading system and we make tapes lighter than anyone does in either marine or aerospace pre-preg. The off-the-shelf lightest materials you can buy are about 80g/sqm and we are making materials down 25-30 sqm routinely and we have made tapes down to 15g/sm.”

Above: The 'Pregger'

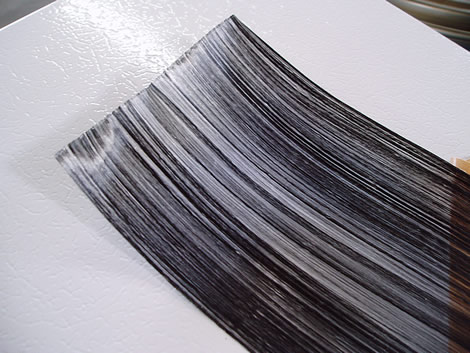

Above: Carbon/dyneema hybrid tape

ii) On to the plotter

Tapes are cut and pre-formed in 2D sail sections known as ‘complexs’ on a ‘flat bed plotter’ using a computerised ‘tape laying head’ and cutter North has developed. This process has to be automated as it would simply take too long to complete manually.

iii) On to the mould

The sections, loosely tacked together on the plotter, are then transported to one of the 3DL three dimensional moulds. Once on the mould the sections are manually lined up using reference marks from the plotter, put inside a vacuum bag with release films and the whole laminate consolidated and thermo-formed on the moulds - this part of the process similar to that of the manufacture of 3DL sails.

Pearson expands on this: “With a 3DL mould we are laying down 13 yarns at a time and they are running in great curved arcs over the surface of the mould and they are running at fairly high speed. But [with 3Di] because the tapes are quite thin and delicate and hard to handle, the heads run at a lot slower speeds and you can’t go around curves, because you are laying down 120mm wide tape. So you have a lot of short sections to lay down and we do that on these flat bed plotters, just like you would lay up sections of prepregs as pre-forms [if you were constructing the hull of a boat]before moving it into a mould.”

So compared to 3DL where the fibres are laid up directly on to the three dimensional mould, the 3Di process has one extra step.

In terms of human involvement in the 3Di process, the most labour intensive part is manually manipulating the sections together once they are on to the mould – the sections join together with a scarf joint – and building the vacuum bag around them.

So what’s the big deal?

Compared to 3DL, 3Di is much stiffer when it is flying as it allows fibres to be laid in a multi-axial pattern. And a sail that is better at holding its shape makes for a superior and more powerful aerofoil.

As Pearson explains: “One of the things we have learned in the last couple of years - and something that we grossly underestimated with all our fancy sail design software - is that there are a lot more compressive forces in sails that weren’t really being addressed. So by having modulus or fibre orientated to all the different load directions is actually giving you an aerodynamically stiffer sail with better shape holding compared to a 3DL sail with the same amount of fibre.

“In a 3DL sail, all fibres go in the load direction. So we have the same amount of fibre in this sail, but less than half of it is going in the load direction and 50% is going in all these other orientations.”

So in short, a wholly different design philosophy to what has preceded 3Di. Pearson confirms: “There is a great big open book there which we haven’t even started to address yet, now that a sail designer can choose any amount of fibre anywhere in the sail in any orientation. There is years of development work still to do.”

Above: TP52 leech

Another difference compared to 3DL is in high load areas of a 3Di sail, the added structure is built internally, rather than externally. According to Pearson the minimum lay-up comprises four layers of tape whereas in the corners there might be 100s. “It has left the textiles industry and we’ve really gone all the way into a composite structure now, albeit a flexible composite.”

The chemistry going into the sails has taken considerable refinement. While North have built around 350 3Di sails to date, the big issue according to Pearson remains the trade off between stiffness and durability. To improve this they are using low stretch, but highly flexible Dyneema– so typically the fibres going into the tape used in a grand prix sail will comprise 70% carbon and 30% Dyneema, while in the sails a tier down from this the balance is 50% between the two fibres. However this still remains an area of substantial development.

The ability to use Dyneema represents another significant difference between 3DL and 3Di as the resins used in the latter, can be cooked at a lower temperature. 3DL cooks at a surprisingly high 150degC, while Dyneema starts to melt at 140-150degC and so can’t be used in the construction of 3DL sails. With 3Di cooking is typically around 120degC or less.

In terms of the resins used, 3Di uses two bespoke systems developed by their exclusive suppliers in collaboration with North’s own chemists/engineers - one on the interior of the laminate a highly elastic polyester thermoplastic while on the exterior is a harder stiffer resin system to provide more smoothness, hardness and abrasion resistance.

“We are using the same resins for all the fibres, so we have that side of it worked out,” says Pearson. “The whole lamination side is actually going quite well without any problems, but it is a question of how long the sails will last in flex and folding fatigue for a given amount of aerodynamic stiffness which comes down to how much carbon you put into it or don’t.”

Read part two here

Latest Comments

Add a comment - Members log in