Raising the benchmark: Groupama C

At last week’s Little America’s Cup, Franck Cammas and his team demonstrated that they had raised the benchmark considerably with their all-conquering catamaran, Groupama C. Wholescale advancement of this kind is likely to become run of the mill if the America’s Cup continues in winged foiling catamarans, as it seems it will. One can easily imagine Cup teams using the 25ft long wing-powered foiling cats for their small scale wing and foil development instead of the SL33s, that the Kiwis and Luna Rossa used for this last Cup, or the AC45s, that Artemis and Oracle Team USA worked on.

With the team freshly returned from having won the Volvo Ocean Race, work on Groupama C got underway in the summer of 2012 with Cammas forming a design team including Martin Fischer, Guillaume Verdier and Benjamin Muyl (both Verdier and Muyl were also part of Emirates Team New Zealand’s design team), plus engineer Denis Glehen and sailmaker Gautier Sergent. They worked in conjunction with Groupama’s in-house design team of Loïc Dorez, Marine Villard, Olivier Mainguy, Pierre Tissier, Edouard Touchard, Stéphane Chatel and Italian trainee Stefano Cacciola.

In developing their new boat, the Groupama team not only acquired Steve Killing-designed Alpha, Canadian Fred Eaton’s 2007 LAC winner and 2010 runner-up in the hands of Jimmy Spithill and Glenn Ashby, but also created a foiling Phantom F18 (another design by Martin Fischer). These were used as test beds for foil and wing development prior to the team launching their new C-Class this summer.

The platform for Groupama C was constructed in TPT (like the Hydros boats) by Multiplast in Vannes, while the wing was built in-house using regular composites. Saying this, judging from how little the Groupama C wing sagged when being carted in and out of the team’s tent last week, it was presumably made in very high modulus carbon fibre. Engineering for the boat was carried out mainly by Guillaume Verdier and Benjamin Muyl.

So what is new about Groupama C? Franck Cammas admits that the boat is complex and it has “a lot of toys”, but aside from being built to win this year’s Little America’s Cup, it is certainly also a test bed for his 35th America’s Cup campaign. Creating the boat provided much insight into designing, engineering and building wings and foils, familiarising the team with the process involved, as well as enabling Cammas to discover how to sail the boat once she was launched.

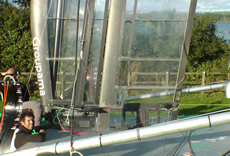

Wing

The wing was developed principally by Benjamin Muyl and Gautier Sargeant. Muyl says that they started using the wing from Alpha as their benchmark: “We did wonder whether we should invent something else, because we had better ideas or if we shouldn’t just try to improve what they did.” In the end they chose the latter option.

Thus the wing on Groupama C has the same basic configuration as the majority of C-Class wings since Steve Clark’s Cogito in 1995 (and the AC72s and 45s), with a front element, a rear element slung off it, with a small flap and the all-important ‘slot’ in between the two.

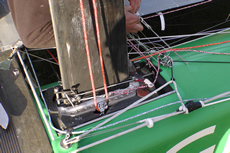

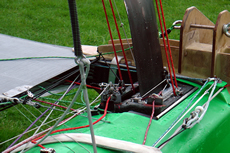

As normal there are three basic controls for the wing: sheet (overall orientation of the wing to the wind), camber of the wing (the angle between the elements and flap) and twist (relative camber up the rear element). As was the case with Oracle Team USA’s AC72, the top of Groupama C’s wing can be completely inverted if it needs to be depowered. Plus twist can also be induced up the front element.

However Groupama C’s wing was unique among the boats in Falmouth (until the finals, when Hydros Lombard Odier added this feature), in that it can be canted. Canting the rig to weather is a feature Cammas has had on all his big trimarans from his ORMA 60s on, as the benefit of hauling the rig’s centre of effort up to the weather alleviates the bow-burying downward force on the leeward bow. On foiling C-Class cats this must also have a beneficial effect on reducing the porpoising of the boat when she’s foiling.

Exactly how the wing canting mechanism works is a secret closely guarded by the team, but in practice going into a tack the wing is dumped to leeward where it is locked in place prior to carrying out the manoeuvre. It can also be locked in a centre position for sailing downwind. In addition to having running backstays there is a handle on each side of the boat presumably used to ease off and take up on the twin forestays. The mechanism for achieving all this is mounted within the wing.

In terms of its aspect, the Groupama C wing is the same height as Canaan’s (ie with a higher aspect ratio than previous wings) and has its area spread reasonably evenly between front and rear elements. Another unique feature of the wing is how its leading edge at the bottom tapers in towards the mast step. “The kink is just to follow the wind sheer. It allows the bottom of the wing to be more flat,” explains Cammas.

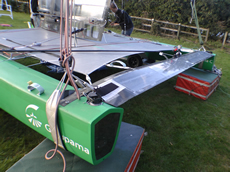

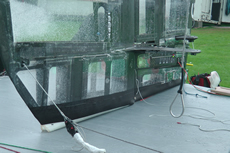

Another significant advance with Groupama C is in her ‘aero’ package. Most evident is the endplate on the wing. Instead of a netting trampoline she has a sheet of 3Di, cranked up so tightly that it probably contributes to the structural stiffness of the platform. Once the wing is stepped, sections are slotted into the bottom of the wing so that when the wing turns there is almost no gap between the bottom of the wing and the trampoline.

Forming an endplate at the bottom of the wing not only harnesses the power of what would otherwise just be turbulence in this area, but has the welcome secondary benefit of increased righting moment. Benjamin Muyl explains: “You have low pressure on the leeward side of the wing that spreads down onto the trampoline to leeward and similarly you have high pressure on the windward side so you create a couple on the trampoline. Plus you have way less induced drag at the bottom of the wing.”

The boat also features fairings on the trailing edge of the main and rear beams, AC72-stylee.

All of these features combined contributed greatly to Groupama C’s incredible upwind pace compared to her competition.

While Groupama C is fiendishly complex, as ever with C-Class catamarans the name of the game is to refine the control lines to make the boat as easy as possible for two people to sail. For example the camber and twist controls are linked (via the myriad of micro-blocks in the foot of the wing) and there is also a system whereby the weight of the crew going out on the trapeze lifts the weather board.

As Muyl puts it: “At some point you need to remove things for the guys, otherwise they cannot race...”

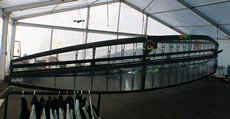

Hull

In terms of her hull shape, Martin Fischer, who worked on “all the parts in the water”, says of how they started this side of the project: “In the beginning we didn’t know too much about the direction to go, because none of us had designed a C-Class before. We checked the rather wide parameter space for the hull shapes and checked lots of options. We also took Canaan and redesigned it.”

From the outset the boat was designed to foil, but according to Fischer the only influence this had was that less volume was required in the hulls (similar to the evolution in the foiling Moths).

The hulls have a fair amount of rocker to help with manoeuvres, and slender bows with the now familiar reverse sheer, wave piercing-type pointy shape. Aft of the main beam the section becomes more slab-sided and flatter at deck level and below the water. “For manoeuvres we need volume there so that the boat doesn’t do a back flip,” explains Muyl of the shape aft – such things are possible with foilers. Muyl adds that forward the section if very flat in order to help ‘skimming’, ie just foiling, upwind. Many of these features have been influenced by the Emirates Team New Zealand AC72 hull shape.

Foils

If the aero-package is one of the main developments above deck, Groupama C’s foil package was the main envy of the C-Class community in Falmouth last week.

Conceived at a time when the AC72s were already foiling, Groupama C was designed from the outset to be fully foiling, but most impressive is her ability to foil with the greatest stability.

Benjamin Muyl explains: “The question was whether we would succeed at this scale because with Emirates Team New Zealand we had experience on smaller boats like the SL33 and it proved way harder to be stable on that than on the big ones, because of the inertia. So when we started to design the foils, we opted for the safe side of the stability, rather than the performance side.”

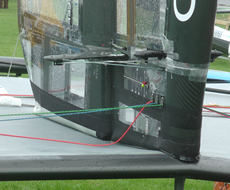

This is partly a function of her T-configuration rudders but also the significant dihedral on her daggerboards (ie the acuteness of the angle between the vertical and horizontal parts).

Martin Fischer continues: “We went for those that showed the best heave stability – you can design foils with less drag, but they are more difficult to handle.” Heave is much the same as pitching moment and in this respect V-configuration foils are typically the most stable, automatically rising up, reducing the lifting surface in the water the faster they go, then dropping down, increasing the lifting surf in the water...and on until an equilibrium is reached. As mentioned in our writing about the AC72s, it is from this side of the equation that Emirates Team New Zealand started foiling, however the V-shape comes with a drag penalty and is potentially not as fast as an L-configuration foil, of the type Oracle Team USA (and the Hydros Lombard Odier) cats used.

Groupama C also seems able to foil upwind in lower wind speeds than we saw with the AC72s and the reason for this is that the C-Class has no limit on board size and as a result the foils, relative to the length of the boat, are substantially larger than they are on an AC72. Of course, the size of the board has other effects on foiling ability that a team must decide upon: a larger lifting surface will enable the boat to elevate from the water in less wind but will offer more drag at high speed, whereas smaller, less draggy boards designed to work at a high speed come with a higher ‘take off’ speed.

According to Fischer, AC teams fitted relatively small boards to their AC72s because they knew they would spend most of the time sailing in decent wind with the boat travelling in excess of 35 knots downwind. “I reckon they ran race models to see what was the optimal size. We also ran systematic, automatic optimisation methods to find the right size of the foils, but at some stage you have to decide how big do you want to go? If they are a bit bigger that gives you an advantage upwind and if they are a bit smaller that gives you an advantage downwind. But we think that at very high speed downwind it is more of a handling problem, therefore you cannot really exploit the theoretical advantage that they have at high speed.”

While the rake of her rudders can be changed (this can be adjusted mid-race – a feature prohibited on AC72s), rake is the only active control for her daggerboards – the case for the boards cannot be manually canted as they are on AC72s. Instead daggerboard cant is induced via the tight S-bend at the top of the daggerboard (like Alinghi 5). When the board is fully lowered it is more upright for going upwind, whereas hoisting the board just slightly cants it ready for sailing off the breeze. Benjamin Muyl says that they chose this technique because there wasn’t enough beam in the hull to be able to cant the daggerboard case adequately, plus their arrangement is lighter. Rake is adjusted based on sea state and wind speed - obviously less rake is required the faster the boat is travelling.

In developing Groupama C, the team went through four sets of boards (and several broken ones allegedly), but according to Martin Fischer, the set the team measured in for use in Falmouth was not that far away from the first boards they designed and built for the boat. “We try to lower the drag of the foils by opening the tip, but we didn’t succeed in getting stable flight,” adds Muyl.

According to Cammas they typically need 6 knots of wind to get up on their foils. This is thought to be possible due to Groupama being fractionally lighter than the Hydros boat.

As ever, the most impressive aspect of the C-Class is how many times faster than wind speed they can sail. Muyl says that in 9 knots of breeze they have managed 27 knots of boat speed and that the record for the boat is 32 knots. Once upon a time these kind of figures were the preserve of the C-Class, but now of course they are being outstripped in most conditions by the AC72s.

Nonetheless the ride is one to be remembered. “It can be dangerous for the boat and the crew!” warns Cammas. “We are very close to the water and we are doing 30 knots at times. It is very impressive.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Latest Comments

wizdeas 02/10/2013 - 20:27

What a technical tour-de force Thanks for the insight. She was tucked away in the tent when I was there on Friday so couldn't get a close view.Add a comment - Members log in