Where next for the foiling Moth?

It has now been more than six years since Rohan Veal gobsmacked the sailing world with his foiling Moth airborne acrobatics. Since then the flying 11ft long singlehander has gone from strength to strength with Moth owners now including America’s Cup sailors like the McKee brothers, Kevin Hall and James Spithill or even Ernesto Bertarelli to the majority of the Australian Olympic team (Tom Slingsby, Nathan Outteridge, Matt Belcher, etc) to offshore sailors like, Seb Josse and Chris Nicholson.

During this time a number of foiling Moths have gone into production, the most successful by far being the Bladerider and more recently, the clear coated carbon fibre (yum) Mach 2. It is estimated that around 400 foiling Moths exist now. Hand in hand with this, performance has improved by as much as 30-40% on some points of sail and the top sailors are all higher and faster than they were upwind and faster and lower downwind.

The market place in foiling Moths is now dominated by the Mach 2 – as an example at the recent Puma Moth World Championship in Dubai, the top 19 boats of the 43 foilers entered were Mach 2s.

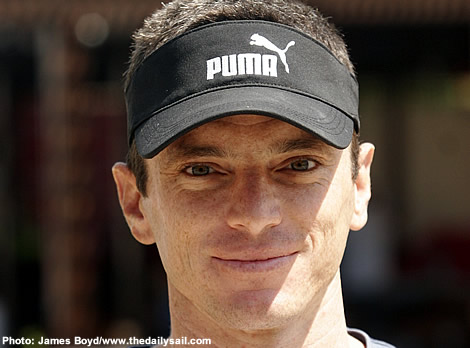

The common denominator to both the Bladerider and Mach 2 are their designer, Andrew McDougall (above), who while he is increasingly becoming known for this role, also runs KA Sails from his base in Melbourne and is also an accomplished foiling Moth sailor.

With the Bladerider and now the Mach 2 so strong in the class, there remain only a handful of smaller manufacturers and, even rarer, individuals such as Dave Lister, still with their own sheds and enough time to innovate. We were going to say it was becoming increasingly hard for them to compete, however Lister has recently come out of the closet with his new Italian-built Monstro design, that appears to be every bit as high tech as the Mach 2. Today homebuilding no longer involves plywood, glue and a lot of optimism, but moulds, ovens, carbon fibre and a lot of skill.

“Dave Lister has done very well with his homebuilds. He is very smart and doing a good job,” McDougall told us, before news of the Monstro had fully emerged. “But it is getting very difficult to do the sort of stuff I am doing on a home build basis, such as building the foils. We are pressurising those things to 20 Bars with moulds that weigh two tonnes and stuff like that. And between the Bladerider and the Mach 2 I have probably spent around nine months full time on the computer just designing the foils - and that’s before we built a prototype! So it is bloody hard work and it took me a long time to better the Bladerider foils. So it is tricky and ultimately only for a very few people is it worth spending time fiddling with things compared to going out sailing and getting in tune with the boat.”

And this is a shame because classes like the Moth, which made the bold step to go airborne, should be about innovation, but thanks to the superiority of boats like the Mach 2, innovation now generally goes hand in hand with being uncompetitive.

Scott Babbage (below), a long term Moth sailor who reckons he has seen this before, believes it won’t last. “We seem to go that way every few years. 10 years ago it was all one designs before the foilers came out. Then they came out and revolutionised things. Now everyone is going for more and more adjustability with their stuff – ride height controls, adjustable gearing, adjustable wands, adjustable rake, so the boats are getting more and more complex with stiff rigs and flat sails. Then someone will come out of left field and simplify all that stuff so that it is automatic and easy and works the shifts better. It goes in cycles.

Sails

KA’s MSL10 and the fuller MSL13 have been out for a while and at the Worlds McDougall unveiled a prototype he calls the MSL15, but ended up not using this as after trying it out on the practice day felt it “was blistering fast upwind, but lacked grunt downwind”. “I have been trying to create a better end plate at the bottom – the way it sits on the boom and a wider luff pocket. Everything is cleaner and more automatic than the current one. A lot of people complain about that the current ones not being automatic – which is what I like, because I can tweak it! – but you have to always be working on your sail.”

At the Worlds, which were held in marginal foiling conditions (in the 5-10 knot range), McDougall said he had learned a lot about his sail. “I’ve just played with cams and cam tensions and I tweaked a few things on the leech, just tightened it up – probably just 1mm with a bit of thread around the mini battens – and the difference was amazing - it really powered up. I put a cam in the very top which I’ve never done before, I never thought it was necessary but I was looking at the flow – I’ve got telltales all over the sails – and the difference was amazing. So I am a lot clearer of where I want to go with the next sail because up until now every time I’ve made something.”

How big thy rudder

At the Worlds, McDougall was also running a smaller rudder and a front foil which he had hand-sculpted. Smaller foils obviously create less drag but also create less lift, requiring a greater skill to use them. McDougall reckons that around 75% of the vertical lift produced by the foils comes from the forward one (whereas the foil on the rudder is more for setting fore and aft trim). “I have seen absolutely no downsides to having a smaller foil, although it has been harder to tack,” he says. “My problem tacking is that I can’t get around the mainsheet and get forward again, so the back tends to sink in the really light stuff – having a bigger rudder gives you that lift.”

People were experimenting with smaller rudders at the Worlds on The Gorge in 2009 when it seemed the reduction in vertical lift wasn’t a problem, although there was deterioration in upwind performance.

At the Dubai World’s Australian Scott Babbage was using a rudder even smaller than McDougall’s – around 68% the size of the standard Mach 2's . “The performance difference in light winds is minimal – I don’t lift off any later than before, but because you aren’t going very fast you aren’t developing a lot of drag anyway,” Babbage explained to us, adding that he is planning to get an even smaller one built too. “It will perform better when it is going faster. I used it in Sydney a bit and it was good there. The only downside is that pitch stability is quite poor, so in waves it is not that flash. Flat water and strong winds it should be great.”

Above rudder size, McDougall says comes the interaction between the sail and the platform. “A lot of people are talking about reducing parasitic drag with the wings, etc. I still think it is early days with that. I’m going go to be working very hard on the whole wand mechanism. I have always been trying to have one setting for everything.”

In Dubai he found that his wand set-up had been completely wrong for the relatively wavy conditions, but has returned home with some new ideas as to how he can make the wand work effectively through a wider range of conditions. This will be introduced for the Mach 2 in due course. He won’t divulge further but it won’t be a variable length wand Mike Lennon was using, nor a centreline wand as tried on several of Adam May's Mistress 3 designs which McDougall reckons creates turbulence down the middle of the boat, nor the twin wand arrangement American ex-49er sailor Dalton Bergen had been trying (which was the original design for the Mach 2). “The biggest issue is making sure you have something that gets you on the foils early and deals with waves and the current systems doesn’t do that – so that is I see some fairly big changes.”

It seems unlikely that McDougall will be coming out with a replacement grand prix boat for the Mach 2 in the foreseeable future. However he does expect to modify parts such as the wand mechanism, along with further foil and sail development.

Getting airborne

The marginal conditions in Dubai clearly showed up those who were good at getting up on foils early and the less skilled who weren’t.

While the inclination is to use maximum flap, decreasing this as you get airborne, McDougall says the secret in marginal conditions is not to use very much flap and to keep it in that same position until you are airborne. Another inclination – to move body weight aft to help the foil’s lift – is also a no-no. “In fact, you probably go forward to keep the boat level, so it is tracking through the water correctly,” he says. “The old bow-up way is wrong. Basically you need nice hull speed and the foils are just lifting and you gradually come up and accelerate and you can time your pumps correctly just to get it up. Usually if you need more than one pump you probably won’t stay on the foils anyway.”

McDougall reckons you need to be going around 6.5 knots to get airborne and it is possible in less than this with a full-on oouch, and then to sail very low, but he emphasises: “You shouldn’t need a massive amount of pumping. We can design these boats so that you can pop it up very easily without all the macho stuff. Yes, you have to point down to do it, which is a loss upwind but if you get on the foils it is a major.”

More Moth foiling fun will appear in Part 2 of this article on Friday

Latest Comments

Add a comment - Members log in